- Art - Culture - Tourism

- Nov 18, 2025

- 23 min read

Updated: Nov 25, 2025

The contrast between Italian and English manners

By Nick Ceramella

21st November 2025

Rome

Photography of Venice and Venice Carnival figures in costume by Theresa Moynes

Photo credit: Theresa Moynes

Venice, a favourite topic in English literature

This article deals with Byron’s poem Beppo as a basis to analyse the social context in which the story takes place. Here we discuss the difference between Italian and English social habits through Michail Bakhtin’s theory of the carnivalesque and the carnival Tradition of Masques and Costumes, and conclude with a brief note on the role that the Carnival has been playing in Venice through the centuries.

But to start with, we shall consider the connection between Venice and English literature. It seems that the name of the city first appeared in English literature in a book entitled The Travels of Sir Mandeville (1371) whose author is anonymous. At the time, Venice is seen as an exotic place where people would go through on their way to the Holy Land. Yet it was not until The Schoolmaster by Roger Ascham (1515-1568) was published posthumously in 1570 that the city began to build its literary reputation as the ideal place where one would go to be introduced to sex and other vices. Ascham says: I learned, when I was in Venice, that there is counted good policy, when there be four or five brethren of one family, one only to marry, and all the rest to welter with as little shame in open lechery, as swine do here in the common mire […] (S, 122)

Illustration from a 14th-century manuscript showing a meeting of doctors at the University of Paris, “by unknown artist, c. 1537. Wikimedia Commons - Roger Ascham. Wikimedia Commons

No wonder that the English youth, invariably coming from rich families, were eager to go to Italy to enjoy themselves and learn what the earthy pleasures of life were all about. But if Venice was a must-go place, most of the Peninsula was not second to the ‘Serenissima’ (a common name for the Republic of Venice), when you come to art, culture, fashion, and social behaviour code (e.g. Baldassare Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano, 1628).

Photo credit: Theresa Moynes

Among the many English authors that contributed to the city’s fame, William Shakespeare (1564-1616) gave a major contribution to take the myth of Venice further along. He focused on the severity of justice in The Merchant of Venice (1620), and on the connection between love and death in Othello (1622). Nonetheless, it is Thomas Nash (1593-1647), who married the Great Bard’s granddaughter Elizabeth Hall, that adds more to the already incredible Venetian legend in The Unfortunate Traveller (1594) in which fornication and deception get master and servant to exchange identities in order to enjoy the Venetian mysteries. Among other authors worth noting, in this respect, are Shakespeare’s friend Ben Jonson (1573-1637), and later Daniel Defoe and Joseph Addison. The interest in Venice grew with Gothic novelists, such as Ann Radcliffe, who set The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) in a Venice she created from pure fantasy. We may say that the apex was reached in the Romantic period, when besides Byron, whom we will focus our attention on shortly, Wordsworth and Shelley enhanced its fame and charm by saying that Venice was an appropriate place to ponder about the eternity of poetry opposed to the passing of time and anything mortal, including the fall of once powerful civilizations. They believed that a moral lesson for the English could come from Venice whose decadence could show them that they too could decay and fall eventually. The novelist

Pictures of Italy by Charles Dickens. Art by Livia Signorini. Tara Books Ltd, UK. Photos: Marysia Zipser

Charles Dickens (1812-70) in his travelogue Pictures From Italy (1844-45) described Venice as an “Italian dream”, a balance of East and West, with an amazing artistic heritage, but at the same time so decadent that it confused one’s perception of it. A similar change of focus on the city can be found in John Ruskin’s masterpiece The Stones of Venice (1851-53). He, like many other English visitors before him, was charmed by its conventional romantic beauty, but after eleven visits there from 1833 to 1845, chose to concentrate on the city’s architecture and art.

John Ruskin, 'The Stones of Venice' examines Venetian architecture in detail.

Ruskin became emotionally and intellectually so involved that he even thought of himself as a foster child of Venice, and gratefully declared in 1851 “Thanks God I am here, it is a Paradise of cities.” In the second half of the 19th century, we should remember Robert Browning (1812-1889), who after his wife Elizabeth Barrett passed away, stayed on alone in the Ca' Rezzonico, one of the most enchanting 18th century palaces (today a museum), overlooking the Canal Grande.

Ca'Rezzonico museum. Photo Didier Descouens.

Wikimedia Commons.

Then, Henry James (1843-1916) used Venice as the setting for the short story The Aspern Papers, and for a considerable part of the novel The Wings of a Dove. He also dedicated the opening essays to the city in his collection Italian Hours, amounting to one quarter of the whole book. In these essays, which were written between 1872 and 1902, James in the essay entitled ‘Venice’ pays due homage to Ruskin after whom he thinks there is not much else to be said about the city, ‘I do not pretend to enlighten the reader; I pretend only to give a fillip to his memory’ (IH, 7).

Portrait of Henry James by John Singer Sargent, 1913. National Portrait Gallery. Wikimedia Commons.

Still, while expressing his admiration for the beauty of the city, which he fears may decay through time just like an ageing woman, or rather any human being, he is in adoration for the place, almost in erotic terms:

‘You desire to embrace it, to caress it, to possess it; and finally a soft sense of possession grows up, and your visit becomes a perpetual love-affair.’ (IH, 11-12)

Later, in the first half of the 20th century, among several other artists, particular attention goes to the German writer Thomas Mann, whose claim to fame is Death in Venice, (Der Tod in Venedig, 1912), and who like James developed the combination of love and death, thus recalling Shakespeare’s theme.

Thomas Mann 1929. Wikimedia Commons.

Equally worthy of note are Ezra Pound (1885-1972) and the Russian musician Igor Stravinsky (1875-1955) who, according to their personal requests, were both buried in their beloved Venice. This long-standing link between Venice and artists, just to think of those from English-speaking countries, has been continued by such writers as David Kalstone, John Malcolm Brinnin, Pier Pasinetti, and Edmund White, as well as travel writers, like Jan Morris, Gore Vidal, and Mary McCarthy. Not surprising then if it is not easy to distinguish between real life and art / literature when discussing Venice.

Lord Byron’s Beppo: A Venetian Story

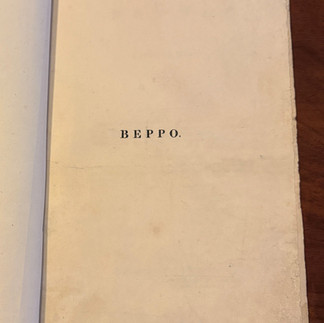

From the first edition of Beppo 1818, Courtesy of Nottingham City Museums and Galleries, Newstead Abbey’.

From an image from the collection of the Palazzo Mocenigo by J Vivian, painted in 1875. Courtesy of Nottingham City Museums and Galleries, Newstead Abbey

Plot of Byron's 'Beppo'

Following this short introduction, now we can concentrate on Lord Byron (1788-1824) and his lengthy poem Beppo. The plot of this entertaining work results from the merging of an anecdote on Venetian life that Byron heard about in Milan from an Irish Colonel, named Fitzgerald, just a few months before he started to work on it in 1817 while he was in Venice. Fitzgerald said that, on returning to Venice after twenty-five years spent in Turkey, he hoped he would get back his lover’s affection, the Marchesa Castiglione. In the meantime, an unexpected problem occurred, not only she had become a widow, but she did not even recognize him; so, to convince her that he was not an impostor, he had to go into details concerning their relationship. The Marchesa was most impressed by his incredible constancy that to show how much she admired him; she presented him with some apartments in her palace. Byron certainly found this story so absurd that referred to it in a letter to his friend Tom Moore, dated 26 December 1816, stressing that it gave him the opportunity to show he was not a monotonous and boring writer but could well write a comic story like that. (See LJB Vol. iv, 26). Legend has it that there was another anecdote circulating in Venice at the time. A Turk returns to Venice and to his surprise finds that the landlady of the inn where he is staying is now some sort of Mirandolina in Goldoni’s fashion. To prove his true identity, he shows her a scar on his shoulder which only the two of them knew about. He tells her he had built up a large fortune in Turkey and was prepared to share it with her. Nonetheless, he gives her three options: leave her present lover and go with him, carry on with her lover, or accept some sort of pension and live on her own. It seems that the plot created by Byron is a merging between the two stories which resulted in Beppo: A Venetian Story. Byron recounts the legend of Laura, a Venetian lady whose husband Giuseppe (or Beppo for short) a sailor, has been lost at sea for the past three years. She mourns him for that period, but eventually, according to Venetian customs, she takes on a ‘cavalier servente,’ a lover, simply called the “Count.” Indeed, he is a noble man, a Count, an accomplished gallant and fashionable man, who can write, sing and dance. She has a passionate love affair with him that continues even after she unexpectedly meets at a carnival ball her missing husband masked as a dark Turkish-looking man, (See social function of disguising in the final paragraphs of this article). He explains that he could not get back home because he was enslaved until he was liberated by some pirates, whom he subsequently joined in their attacks. After gathering a substantial amount of money, he left the band of outlaws and returned to get his wife back, and most importantly had to be re-christened.

Photo credit: Theresa Moynes

It may sound weird to most readers to see that the story settles down into a comfortable ‘ménage à trois’ instead of the typical English way with a duel, divorce, and ostracism. Of course, if one does not know about the Venetian customs of the time, one is puzzled to see that Laura re-joins Beppo, while her extramarital relationship goes on as if nothing had happened.

England (London) and Italy (Venice), two worlds apart

But let’s be as practical as Byron himself, Beppo, which is subtitled A Venetian Story, cannot but be an account about Venice and Venetian ways, bound then to be imbued with the deep spirit of local life with its frivolous joy and lavishness. Consequently, the story told in the poem is systematically contrasted with England and English ways. Byron, who is familiar with both worlds, matches them against each other. Hence, there are lines like the following when the poem sounds even like a letter written from Italy to a possible correspondent in England:

It was the Carnival, as I have said

Some six and thirty stanza back, and so

Laura the usual preparations made,

Which you do when your mind’s made up to go

Tonight to Mrs. Bohems’s masquerade,

Spectator, or partaker in the snow.

The only difference known between the cases

Is – here, we have six weeks of ‘varnish’d faces.’

(Stanza LVI)

Most interestingly, this stanza shows that Byron, though he had been away from England for a number of years, kept himself up to date about life in England by reading the Morning Chronicle, a popular London newspaper. Thus, he must have read about a masquerade taking place on 17 June 1817, at Mrs. Boehm’s, a London lady, who organised such feasts, lasting ‘one evening’ only, whereas in Venice they lasted as many as six weeks. Italy was indeed a living theatre where life was lived intensely. Likewise, Byron describes the awkwardness of an English girl’s ‘coming out’:

‘Tis true, your budding Miss is very charming,

But shy and awkward at first coming out,

So much alarm’d, that she is quite alarming,

All Giggle, Blush; half Pertness, and half Pout.

And glancing at Mamma, for fear there’s harm in

What you, she, it, or they, may be about,

The nursery still lisps out in all they utter –

Besides, they always smell of bread and butter.

(Stanza XXXIX)

It is self-evident that Byron meant to ridicule the usual English women’s sexual embarrassment as opposed to the refined and solar attitude of Venetian women that he had become so familiar with.

Photo credit: Theresa Moynes

This explicitly triggers the poem’s main merit which lies in its comparison of English and Italian morals (of the time) showing that the English aversion to adultery may be seen as mere hypocrisy in light of the probably shocking but more honest custom of the more pragmatic acceptance of the Italian ‘Cavalier Servente,’ a role in which Byron became an outstanding example with his ever open sexual affairs as that with Marianna Segati and Margherita Cogni in Venice, or Countess Teresa Guiccioli in Ravenna.

Byron and Marianna Segati, from lithograph by William Drummond, engraving by George James Zobel. Courtesy of Nottingham City Museums and Galleries, Newstead Abbey.

Teresa Gamba Guiccioli, by Lorenzo Bartolini (1777-1850,) marble, 1821. At Museo Byron e del Risorgimento, Ravenna. Photo credit: Stuart Baird

With respect to that, it is interesting what R. D. Waller remarks: ‘The shadows of chivalry give place to the living world. For King Arthur’s feasts, we have the Venetian carnival; for fabulous knights and giants, amorous men and women.’ (MG, 51) Therefore, reading Beppo is like experiencing two opposite lifestyles, with their respective drawbacks which, for instance, emerge when Byron makes fun of English snobbery counterbalanced by the vulgarity of Italian noblesse. Or, when he highlights the fact that in Southern Europe in general, they accept that a married woman has a lover even if certain conventions are still to be followed. Paradoxically, a man must observe his family obligations and be faithful to both his lover and his wife. However scandalous this arrangement must have appeared to English people, that was a practical option which Byron certainly enjoyed presenting to this countrymen while emphasizing they had no reason to claim a superior morality since they quite frequently divorced. At least at the time, men could easily divorce their wives, while women had to catch their husbands in the sexual act and even offer proof of that. Indeed, a very complex thing to do. Be that as it may, besides the interest in the Venetian way of life,

Photo credits: Theresa Moynes

Beppo a turning point in Byron's life and literary career

Byron was determined to write a lengthy poem to mark his first attempt at using the Italian ‘ottava rima’ metre, characterized by a colloquial rhythm and a rhyme. His intention to realise the voicing of a substantial variety of moods that reflected the exuberance, the informality, and the humour present in Byron’s journals and letters. In fact, this reflected a lesser known side of his personality which apparently worried him, and, in the spring of 1817, got him to send a letter to his best friend Thomas Moore to reassure Jeffrey, one of his favourable critics, by saying:

‘I was not, and, indeed, am not even now, the misanthropical and gloomy gentleman he takes me for, but a facetious companion, well-to-do with those with whom I am intimate, and as loquacious and laughing as if I were a much cleverer fellow.’ (LJB, 328).

It is obvious that Byron was worried about his public image and wanted people to know him as he really saw himself, or rather let them know the humorous side he preferred of his personality. In the autumn, in order to promote that image, he began to write Beppo, where he, while trying to catch the essence of the flavour of his Venetian experience, as he does in his major poems Don Juan and Child Harold’s Pilgrimage, also mixes some autobiographical elements with the fictional ones. Noticeably, he was writing his memoirs in about the same period he was working on Beppo, which explains why he acknowledges in two occasions that the real story about himself can be told only in prose as he says ironically about his wife Isabella, without mentioning her on 17 June 1817:

Why I thank God for that is no great matter,

I have my reasons, you no doubt suppose,

And as, perhaps, they would not highly flatter,

I'll keep them for my life (to come) in prose …

(Stanza, LXXIX)

But in truth, in Stanza LII, while still digressing about his life, although tempted to use prose, he opted for poetry mainly because that was the fashion of the moment:

But I am but a nameless sort of person,

(A broken dandy lately on my travels)

And take for rhyme, to hook my rambling verse on,

The first that Walker's lexicon unravels,

And when I can't find that, I put a worse on,

Not caring as I ought for critics’ cavils.

I’ve half a mind to tumble down to prose,

But verse is more in fashion – so here goes.

(Stanza LII)

Although Byron is the hero of this stanza, he mockingly says that not only he is a failure as a poet but also as a fiction writer, just a little more gifted for prose. Self-derision is also the device he uses to justify his mockery of others, as he did above in writing about his wife’s intellectual pretension. But what is particularly interesting here is that it seems he was also prepared to reconsider his own doings and radically change his lifestyle. Hence, it is not incidental that Byron wrote Beppo in the autumn of 1817, coinciding with the time is when he abandoned arrogance, with its debaucheries which had characterised his youth, and became tired of fiery passions and despairs and realised that he enjoyed the mild tolerance of Venetian life. Afterwards he began to behave with a certain moderation. Most interestingly, this emerges from the cheerful and irreverent tone that marks his literary work. It is the same tone that we find in his letters, revealing a very enthusiastic and determined observer of human comedy. But the man suffering and the creative poet are both mocked by himself and best seen also in some short poems like “So we’ll go no more a-roving.” This lovely poem was written in February 1817, at the end of Byron’s first carnival season in Venice, and was included in a letter to Thomas Moore on the 28th.

Photo credits: Theresa Moynes

It denotes that the man at twenty-nine was no longer eager to sustain the pursuit or exploration of sex, when he used to go swimming home along the Grand Canal after a ball, with his servant rowing behind him to carry his clothes. These lines were written during Lent, showing in a sense that Byron was prepared to change his libertine approach to life.

So, we’ll go no more a-roving

So late into the night

Though the heart be still as loving

And the moon be still as bright.

(WLB, 100)

By the autumn of 1818, he accomplished Beppo which appeared anonymously in England in the same year. It anticipates by one year Don Juan, a much longer poem covering three years in a vast geographical area, while the other one covers only a Carnival evening in Venice. Byron wrote it when he was in a desperate and wild mood, and consoled himself, although exhausted, with a kind of bitter bawdiness. He brilliantly described his state to his friends Thomas Moore and John Murray in some letters like the following, written in Ravenna on 21 Feb 1820:

[…] I have lived among the natives – I have lived in their houses and in the heart of their families – sometimes merely as ‘amico di casa’ and sometimes as ‘amico di cuore’ of the Dama – and in neither case I feel authorized in making a book of them. — Their moral is not your moral – their life is not your life – you will not understand it – it is not English nor French – nor German –which you would all understand – the Conventual educational – the cavalier Servitude – the habits of thought and living are so entirely different – and the difference becomes so much more striking the more you live intimately with them – That I know not how to make you comprehend a people who are at once temperate and profligate – serious in their character and buffoons in their amusements – capable of impressions and passions which are at once sudden and durable […] (LJB, 413)

Origins and role played by Carnival

For the purpose of this article, it is important to underline the role played by the carnival festivity. As hinted in the opening of Beppo, the first stanza announces Byron’s unconventional intentions and sets also the scene for his Venetian story by giving some information about the meaning of Carnival in Catholic countries where for a day the event helps to pull down social, religious, and economic barriers alike, regardless of the participants’ background:

'Tis known, at least it should be, that throughout

All countries of the Catholic persuasion,

Some weeks before Shrove Tuesday comes about,

The people take their fill of recreation,

And buy repentance, ere they grow devout,

However high their rank, or low their station,

With fiddling, feasting, dancing, drinking, masking,

And other things which may be had for asking.

(Stanza I)

As a final touch, Byron enthusiastically evokes the typical carnivalesque atmosphere in town, when people from all walks of life get ready for the event, and says that lovers take advantage of the night without any restrains, “The time less liked by husbands than by lovers/ begins, and prudery flings aside her fetter.” (Stanza II) Then, in the next stanza, he refers to the masks featuring all times and countries. He ironically warns the “Freethinkers” that getting dressed as a priest was not a welcome choice, because carnival was meant as an absolutely lay and licentious event. Therefore, religion should be left out of it.

And there are dresses splendid, but fantastical,

Masks of all times and nations, Turks and Jews,

And harlequins and clowns, with feats gymnastical,

Greeks, Romans, Yankee-doodles, and Hindoos.

All kinds of dress, except the ecclesiastical,

All people, as their fancies hit, may choose,

But no one in these parts may quiz the clergy, –

Therefore, take heed, ye Freethinkers! I charge ye.

(Stanza III)

Eventually, in line with all the above, it is appropriate to cite just one more Stanza since it stresses why Venice, especially during Carnival, is the ideal place for affairs like that narrated in Beppo to happen:

Of all the places where the Carnival

Was most facetious in the days of yore,

For dance, and song, and serenade, and ball,

And masque, and mime, and mystery, and more

That I have time to tell now, or at all,

Venice the bell from every city bore

And at the moment when I fix my story,

That sea-born city was in all her glory.

(Stanza X)

Michail Bakhtin's theory of Carnival

t this point, a question arises quite naturally. What is the origin of carnival and its relationship with Venice? As well as the origins of carnival itself and its connection to literature, the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin elaborated a most intriguing theory which answers this question. In Rabelais and his World, he introduces the meaning of carnivalesque (or folk-humour), that is the spirit of the carnival

Mikhail Bakhtin - François Rabelais - Statue in bronze by Pierre Eugène Emile Hébert. 1882, Chinon.

Wikimedia Commons

changed into the carnivalesque by which he meant its rendering into literary form. In the introduction to the book, Bakhtin describes the world-famous French writer François Rabelais (1494-1553) as a figure who shunned the categories of western liberal humanism:

He cannot be approached along the wide beaten roads followed by bourgeois Europe’s literary creation and ideology during the 400 years separating him from us […] To be understood, he requires an essential reconstruction of our entire artistic and ideological perception, the renunciation of the many deeply rooted demands of literary taste, and the revision of many concepts. (RHW, 3)

As Bakhtin elaborates, there is a tradition of folk humour whose roots are in pagan rites of fertility and rebirth that continued to exist as a second world alongside the first institutional ‘official’ world of the predominant power. This other unofficial world mocks and mimics the institutional one, represented by folk festivals like the carnival. In Bakhtin’s words: ‘Carnival is the people’s second life, organised on the basis of laughter. It is a festive life [in which] people for a time enter the Utopian realm of community, freedom, equality, and abundance.’ (ibid. 8-9) Thus, the greatest example of this genre is Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel for its foul and violent language, vitriolic satire, and exaggeration in every aspect. This type of literature and carnival as such broke any restraints, subverting the ordinary rules and laws imposed by the church and the state, although only temporarily, that is during the festivities. Bakhtin traced the origin of the carnivalesque to the concept of carnival related to the Feast of Fools. This was a medieval festival, involving everybody’s creative active participation, which used to be held in the cathedrals by the sub-deacons especially in

Lincoln Cathedral. Photo credits: Marysia Zipser

France, but also in Lincoln Cathedral and Beverly Minster in England. During Carnival all social, ideological, religious, and economic barriers are supposed to fall, so ordinary everyday rules are suspended for balls and parades (mainly over ‘Mardi Gras’ which is simply a show in its own right). This overturning of hierarchies and transgressing of boundaries resulting in new syncretic forms has been strongly theorised by Bakhtin whose work provides an important template for contemporary thinking about cultural forms. In brief, this is synthesized through his four categories of the carnivalistic sense of the word, when all the following was allowed and encouraged:

1) Familiar and free interaction between people: the interaction between the most different people was welcome and encouraged.

2) Eccentric behaviour: everything that was usually considered unacceptable was encouraged.

3) Carnivalistic misalliances: carnival time permitted the most unnatural unions such as young and old, Heaven and Hell, the reunion between a man and his wife, although they had a lover when separated.

4) Sacrilegious: even disrespectful actions against the sacrality of the Church was thought to be accepted without any sort of punishment. This aspect links to the origin of cin general, and goes as far back as the Latin Saturnalia of ancient Rome, and the Greek Dyonisia cults. In the Saturnalia the different social layers were dropped and free citizens and slaves mingled indistinctively. Similarly, the representation of plays in Ancient Greece was meant to unite people with nature in a divine harmony, without any limits imposed by social conventions.

Having presented the very roots of the festival by passing to the Carnival of Venice, we know that it is related to the victory of the Republic of Venice against the Patriarch of Aquileia, Ulrich of Treven in 1662. To celebrate the event, Venetians danced all day in San Marco Square. The festival was

Photo credits: Theresa Moynes

repeated over and over again until it became official in the Renaissance. In the following centuries it became an event – known all over the world – marking the prestige, serenity of the city, thus showing an image of absolute freedom to do anything that one would normally do in everyday life. It was a true appointment with enjoyment without restraints. To encourage that licentious behaviour people were allowed to wear masks which made them feel protected from any kind of retaliation, due to their uncontrolled behaviour. Indeed, masks have always been an important aspect of the Venetian Carnival. Traditionally people were allowed to wear them on Ascension, from Saint Stephen’s Day (26 December) until the end of carnival at midnight of Shrove Tuesday, that is the day before Ash Wednesday.

The “Bauta” mask shown at the Carnival of Venice. Wikimedia Commons.

Social importance of masks in Venice

On ending this article, we need to focus on the importance of the mask in the Venetian society, which also explains why mask makers enjoyed a special social status in society. Wearing a mask had highly political and social implications. Byron knew that well and did not fail to perceive that aspect and dedicated this aspect to his first play Marino Faliero Doge of Venice. He was fascinated by this renegade Doge with the truly Venetian element of carnival. The play opens with a dark representation of a carnivalized state governed by a doge reduced to a puppet, while the power is in the hands of a masked disquieting noble council. The failure of the coup d’état is seen as a carnival event, restoring the social order, while the doge’s rebellion against the state as the highest member in rank is an act of self-carnivalization. Therefore, wearing a mask was a conventional must, which by preserving you from being recognised allowed you to appear in front of people, as is the case with Beppo who takes courage and goes to the Carnival ball to talk to Laura.

Byron by Joe Ganech. Digital artwork on canvas, 30 x 30 ins., Private collection..

ACT 'Out There' Exhibition of International Artists, 21-29 April 2017, Nottingham

Nick Ceramella

Rome

Bibliography

S. John William Hebel (ed.), Prose of the English Renaissance, The Schoolmaster Book I. New York: Appleton-Century-Croft, 1952, p. 122.

Henry James, Italian Hours, ed. & introduction John Auchard. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1995.

BLJ Leslie A. Marchard (ed.), Byron’s Letters and Journals, Vol. IV (1814-15). Harvard: Harvard University Press, retrieved 27 December 2017.

MG R. D. Waller (ed.), Introduction to his edition of The Monks and the Giants. Manchester: The University Press, 1926.

WLB Lord Byron, Beppo, in The Works of Lord Byron. Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 1994.

RHW Mikhail Bakhtin [1941], Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Nick Ceramella has been the Vice-President of the D. H. Lawrence Society of GB since 2019. He is a professor of English Literature and Language, and Translation Studies. He taught at the following Italian universities: La Sapienza Rome, SISS Roma Tre, LUMSA - Roma, University for Foreigners - Perugia, Istituto Universitario l’Orientale Naples, SICSI Federico II Naples, University of L’Aquila, and the University of Trento. Nick has also served as Visiting Professor at the Russian State University for the Humanities of Moscow (Russia); the Federal University of Maçeió, Alagoas (Brazil); University of Minsk Belarus; University of Nikšić, Montenegro, University of Tirana (Albania).

He has lectured in most European countries, in the USA (Brook University - NY), in Kyoto (Japan), and Lahore (Pakistan). He has organised and was keynote speaker as well as chairman at conferences worldwide.

His eclectic publishing and teaching are reflected in his wide variety of books and articles on English literature (Renaissance theatre and Modernism), ESP (media studies), Italian American literature, Theory and practice of translation, and History of the English language.

His latest publications (2023) include: Marriage between Literature and Music, Insights into D. H. Lawrence‘s Sardinia, Domenico’s New Year di Francis Thomas Galwey (translation, introduction and notes). Nick Ceramella photo credit: Nigel King, 2023

This article is published by Marysia Zipser, Founder of Art Culture Tourism & ACT Ambassador,

https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/ https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/blog E: artculturetourism@gmail.com / marysia@artculturetourism.co.uk

Please feel free to write your feedback remarks/reactions to Nick in the Comments box below to which he will respond, and to share/forward this article link via email to friends, colleagues and to socials as you wish. Thank you.

Useful Links:

Byron Societies Worldwide:

https://www.internationalassociationofbyronsocieties.com/ IABS est. 1971

https://byronsociety.org/ Byron Society of America est. 1995

https://byronsociety.org/recent-posts/ - News - Call for Papers 2026

Notable national societies include the Byron Society of America, the Japanese Byron Society, the French Byron Society, and the Newstead Abbey Byron Society. These organisations host international conferences, publish journals, and organise events to celebrate Byron's legacy.

Other societies: There are many other societies around the world, including in Canada, Italy, and Greece.

Please read/refer to past ACT articles on Byron:-

https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/post/england-italy-the-byron-connection-newstead-abbey-and-ravenna July 18, 2025 by Stuart Baird

October 26, 2024 by Janine Moore

https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/post/the-inauguration-at-palazzo-guiccioli-ravenna-of-the-byron-museum-and-museum-of-the-risorgimento August 31, 2024 by Patrizia Poggi

https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/post/byron-200-byron-s-bash-and-vyronas-nottingham-agreement April 30, 2024 by Marysia Zipser

- Art - Culture - Tourism

- Nov 7, 2025

- 8 min read

By Peter Clarke LRPS

7 November 2025

Beeston, Nottingham

Photography by Peter Clarke.

As a family we all love Italy. The food, the culture and the history. We have visited many regions and many cities. Rome the eternal city, Bologna, Venice, Florence and Pisa, and Lecce in the south.

This year we decided we would take in the sights and history of the Ligurian coast and had our base in Genoa. It is also known for its historical association with international celebrity and artistic visitors; writers and poets like Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, DH Lawrence, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, Ezra Pound,, Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, who were inspired by the beauty and spirit of Liguria.

I had booked an apartment on Via XX Settembre which was fairly central and within a 15 minute walk to Genoa Brignole station for getting further afield.

Our first day was taken up by a very pleasant walk along the coast to Boccadasse, a former fishing village which is now a beautiful seaside town. From Genoa it is roughly 5 km and should take you around an hour to walk.

Bagni San Nazaro - Church of St Anthony and promenade

Along the coast road there is a well maintained promenade with some lovely views of the coastline and fantastic villas.

The first main sight you will come across walking into Boccadasse is the Church of St. Anthony of Boccadasse. The church was built in the 17th century as a chapel by fishermen and by the inhabitants of the area. After a few decades in 1745 it became the seat of the confraternity of Saint Anthony of Padua and in 1787, after enlargement, was officially considered a church. It is a very peaceful and pretty church worth stopping off at for rest, prayer or just to feast your eyes on simple Italian architecture.

Moving on around to the rear of the church you will be presented with the sight of Boccadasse beach and some of its many pastel painted buildings.

We had an appetising lunch of octopus salad and calamari at Antica Osteria Dindi, a charming restaurant with both inside and outside seating areas. A little bit more expensive than other restaurants we came across but reasonable value for money. https://www.tripadvisor.it/Restaurant_Review-g187823-d1725969-Reviews-Antica_Osteria_Dindi-Genoa_Italian_Riviera_Liguria.html

Heading out of the beach area it is a reasonable climb up to the main part of the town.

When you are high up in the main town you are treated to fabulous architecture and wonderful panoramic views of the coastline.

I love the way the Italians keep their rich architectural history by retaining what look like run down buildings from the outside but are renovated on the inside.

The next day we moved along the coast to take in what we had really come to this area for - the “Cinque Terre”.

As the name of the area translates into English, it is an area made up of five lands or more literally five villages. These colorful, terraced villages—Monterosso, Vernazza, Corniglia, Manarola, and Riomaggiore—are nestled on steep cliffs overlooking the Mediterranean sea and are part of the protected Cinque Terre National Park. We caught the train from Genoa (Genova Brignole) to Levanto where you can then take the Cinque Terre Express which runs between all of the villages. The Cinque Terre Express also goes further than the five villages and onto La Spezia, which some say is “the sixth village” and is well worth a visit. We took the express to La Spezia and then worked our way back up to Levanto.

The town of La Spezia is far larger than any of the villages in Cinque Terre and is full of thrilling architecture, the Technical Naval Museum, and St. George’s Castle which houses an archaeological museum with artifacts from prehistory to the Middle Ages. The nearby Amedeo Lia Museum exhibits paintings, bronze sculptures and illuminated miniatures in a former convent.

Unfortunately we didn’t have the time to visit any of the museums in La Spezia or Genoa. The weather was far too good to be inside when there is a wealth of wonders to view outside – perhaps the next time!

Heading through La Spezia to the coast we came across two sculptures, the first was of Richard Wagner by Russian artist Aidyn Zeinalov and donated to the city on March 16th 2019. Wagner composed the prelude to his opera Das Rheingold, the beginning of his famous Der Ring des Nibelungen tetralogy in 1853 and is often referred to as the "La Spezia vision".

The second and much larger statue is of Giuseppe Garibaldi by Antonio Garella and can be found in Giardini Pubblici. The statue is made of bronze and weighs 60 tons. It is one of the few equestrian statues in the world with a prancing horse, standing only on its hind legs.

Moving on we came across this wonderful art deco building designed by architects housing the Theatre Civico in Piazza Mentana.

The original theatre was constructed between 1840 and 1846 but demolished in 1930 and replaced with this design by Franco Oliva between 1932 and 1933.

Walking through the town to the coast you eventually come to what is now a busy port area housing many boats and yachts and you can regularly see cruise ships moored.

We jumped back on the Cinque Terre Express and alighted at Riomaggiore, said to be the most romantic village. From here you can walk along from Riomaggiore to Manarola in around 30 minutes by taking the Via dell’Amore, Lover’s Lane, a wonderful path known for its romantic atmosphere and amazing landscapes. The Via dell’Amore, is the most famous and romantic stretch of the Cinque Terre coastline. It is a paved, flat walking path, not so much a hike but rather a pleasant stroll affording spectacular views of the cliffs and the sea. It is equipped with handrails and benches along the way making it ideal for inexperienced hikers.

You have to reserve and pay an entrance fee to walk this scenic path. The visitors enter from Riomaggiore going toward Manarola on a one-way route. During the tour, visitors are able to marvel at the gorgeous Ligurian Sea while guides share the story of the Via dell’Amore. It is not included in the Cinque Terre card and costs €10.00.

There are four main sites in Riomaggiore - The Church of San Giovanni Battista, built 1340 in gothic style; The Church of San Lorenzo, built in 1338, with its beautiful rose window dating back to the 14th century; Castle of Riomaggiore, built in 1260, and the Sanctuary of Madonna di Montenero. Due to time restrictions we didn’t explore these.

Moving on from Riomaggiore, our next stop was Manarola built on a high rock 70 metres above sea level. It is one of the most charming and romantic of the Cinque Terre villages and one of the most photographed.

There is a boat ramp, a tiny piazza and picturesque multicoloured houses facing the sea in this tiny harbour village.

Our next stop was Vernazza, we missed stopping at Corniglia.

Our final stop in Cinque Terre was Monterosso Al Mare the largest of the five villages. It has much more of a seaside feel to it having several beaches. Some are public and some are private. Near the station you will find Bagni Eden, the beautiful beach recognized by its orange and blue striped umbrellas.

A trip to this area would not be complete without visiting the upmarket and expensive Portofino. We took a lovely full day boat trip visiting Camogli, San Fruttuoso and Portofino.

Camogli

San Fruttuoso

Portofino

A little bit about our base, the city of Genoa. Genoa is like all Italian cities, it has its beautiful areas and its old run down areas. Being a busy port it has a coastline as well.

Piazza De Ferrari is the main square of Genoa. The square is named after Raffaele De Ferrari, Duca di Galliera, a politician and banker who in 1875 donated a considerable sum for the enlargement of the port. It is the meeting point between the old city and the “modern” Art Nouveau area of Via XX Settembre, one of the city’s main streets that converges on the square. In the centre stands a monumental circular bronze fountain, built in 1936 by the architect Cesare Crosa di Vergagni and donated by the Piaggio family. The fountain was enriched in 2001 with additional water features.

The piazza houses the Teatro Carlo Felice, one of the most famous opera houses in the world.

Genoa street scene - Casa Columba - San Donato, Genoa

For meals in Genoa we stumbled across Osteria della Piazza

Home | Osteriadellapiazza on our way home from our boat trip. It was around 10.00 pm and nowhere else was open. There were plenty of choices on the menu but we all went for pizza and what fantastic pizzas they were – can definitely recommend this restaurant.

We found a beautiful local restaurant called Rustichello OSTERIA RUSTICHELLO. Family owned for over 50 years and the food, wine and service were fantastic, so good we dined there twice.

We also managed to catch the World Press Photography exhibition being held worldwide https://www.worldpressphoto.org/ The exhibition was housed in the beautiful Palazzo Ducale. The exhibits were some of the 59,320 submissions by 3,778 photographers from 141 countries entering the annual competition. The competition rewards professional photographers from all over the world who, during the previous year, took pictures providing an authentic, accurate and engaging insight into the present time.

There were many thought provoking images that we rarely see in the day to day media that we are bombarded with. A shocking fact is that at least 103 journalists across 18 countries were killed last year, with 70 percent killed by Israeli armed forces.

How to get there

There are direct flights to Genoa from the UK - London-Gatwick (British Airways), London-Stansted (Ryanair), Manchester (seasonal) - and the airport is only about a 30 minute drive from the city centre. Alternative routes would be to fly into Milan (or Bergamo via Ryanair) or Turin and catch the train over to Genoa. Railfares are reasonable (cheaper than the UK) and the rail network is excellent with comfortable carriages and on time services.

Another option to bear in mind is that there are regular flights from the UK to Pisa, and you can drive a hired car from the airport, or take the train from Pisa Centrale towards Genoa along the Tuscan and Ligurian coastlines. This railway line (managed by Trenitalia) runs through many towns like La Spezia and connects to the scenic Cinque Terre region.

Genoa is a hidden gem. Often it is overlooked by tourists in favour of more crowded destinations like Rome or Venice. There are grand palaces a-plenty, many of which are now UNESCO World Heritage sites - in fact there are forty-two! Genoa's alleyways, called "Caruggi," are a medieval maze of narrow, winding streets in the historic centre known for their unique atmosphere, artisan shops, and historical significance…and considered the “soul” of the city.

The Ligurian coastline simply sparkles and spreads its magic wherever you tread and explore.

I hope you enjoy reading my travelogue and enjoy seeing my photography. Thank you.

Peter Clarke LRPS

Peter Clarke LRPS, based Beeston, Nottingham, retired early from the electronics industry after 44 years. He now has more time to pursue his passions of photography and travelling. Taking photos for over 50 years both on film and digital, he likes to shoot film with a couple of medium format cameras that have joined his ever increasing arsenal of photographic equipment. He is currently studying for an HND in Photography and has started volunteering as a committee member for the East Midlands region of the Royal Photographic Society. He gained his Licentiate of the society back in May 2013 so can now proudly put LRPS after his name.

Peter also helps charities, Pancreatic Cancer UK and Mencap, having photographed the London Marathon for both charities, the Great North Run and some local events for Mencap.

Useful Links:

https://rps.org/ Royal Photographic Society

This article is published by Marysia Zipser, Founder of Art Culture Tourism & ACT Ambassador, Beeston, Nottingham, UK. https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/ https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/blog

Email: artculturetourism@gmail.com

Please feel free to write your feedback remarks/reactions to Peter in the Comments box below to which he will respond, and to share/forward this article via email and socials as you wish. Thank you.