- Art - Culture - Tourism

- Oct 24, 2025

- 15 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2025

By Janine Moore

25th October 2025

All photography by Janine Moore. Click on photos to enlarge.

Take a walk with me to wander the green lanes and mossy stones of Dale Abbey, Derbyshire — where a 13th-century Premonstratensian house once stood, a hermit carved a cave in the sandstone, and footpaths weave through evocative ruins, an ancient church, and haunted woodland.

The beautiful Dale Abbey Village is nestled in a Derbyshire valley and founded on faith, compassion, and community spirit.

Photo taken at an elevated position showing the east window abbey arch to the lower right-hand side.

Some places make you want to slow down and take in the surroundings. Dale Abbey (once called Depedale or Deepdale) is one of those places: a village of soft hills, a single proud stone arch from a dissolved monastery, a quiet ancient church, and a hidden hermit’s cave tucked into a bowl of woodland. For writers, artists, and walkers, romantics and local-history lovers, Dale Abbey is a pocket of time — a place where the past keeps excellent company with the present. Below I’ve stitched together the stories, the history, and practical walking notes so you can plan a visit that’s equal parts curiosity and calm.

The remaining east window of the Premonstratensian Abbey

A short history of Depedale — the abbey that once stood here and changed the village name

The religious heart of the place began as a hermitage, which drew spiritual attention during the 12th century; from that seed grew a formal monastic community. The house eventually became a Premonstratensian abbey (the “White Canons”) and was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Its probable consecration date is recorded around 1204; though there were three attempts between 1145 and the late 12th century to establish an abbey in the dale.

In 1145, a party of Augustinian monks travelled from Calke Priory. Some twenty years later, Premonstratensian canons from Tupholme and, a few years afterwards, another group, this time from Welbeck Abbey. Most of the failed attempts were due to the surrounding land being unsuitable for their intended use. The thick woodlands and marshy grassland were not good for arable farming. Eventually, by the year 1199, the abbey became more established and was able to gain more land, properties, and tithes.

During the 12th century, Tupholme Abbey sent canons to help establish and support the new settlement of what we now call Dale Abbey (Depedale).

This all enabled the abbey to sustain itself for the following three hundred and forty years. It became self-sufficient and eventually owned roughly twenty-four thousand acres of land. A lot of it would have been leased out to local farmers or used for their own purposes, grazing or producing food for the residents of the abbey.

Even at the best of times, this sizeable abbey only housed twenty-four canons, including the Abbot, and would have dropped to as few as sixteen sometimes.

The community remained here until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII in 1538, when the abbey was suppressed and largely dismantled. Today, very little of the original complex survives above ground — the most striking remnant is the tall stone arch of the east window that frames the landscape like a Gothic picture-frame. This has been a favourite spot for many of my photographs in all seasons and all weather conditions. This place has such a calm feeling about it that I can’t explain.

Even after dissolution, the stones of Dale Abbey found new lives in nearby houses, farm walls, and manor houses: it’s a common local tale that many village buildings carry the abbey’s carved stones and masons’ marks. Historic England recognises the ruins as a scheduled monument — a reminder that, even as nature quietly reclaims the site, the abbey’s significance is formally protected.

The Hermit’s cave external and internal photos.

The hermit’s cave — a carved refuge and a little chapel

One of the most evocative features nearby is the Hermitage (often called the Hermit’s Cave) in the pocket of woodland north of the ruins. The story passed down in guidebooks and local tradition tells of a man, a baker in the 12th century, who claimed to have had a vision of the Virgin Mary and withdrew to live a life of prayer there. It is said that the baker came from the parish of St Mary's in Derby. He had always cared for the poor and was a devout member of the church; he was compared to the Biblical Roman, Cornelius. During a midday nap, he had a vision of The Blessed Virgin Mary, who is said to have given him a message from God that he had pleased him with such work and devotion.

Internal photo of the Hermit’s cave showing the carved cross on the left-hand side of the dwelling

The message guided him to a place called Depedale, and that he should continue to serve God there, in the most bare basic conditions. The baker left all of his possessions in Derby and set out to find Depedale, which he had not heard of before. The story says that when he reached the village of Stanley, he had overheard a conversation between a mother and daughter speaking about taking cattle to Depedale. He asked further about it and accompanied the daughter and cattle to Depedale. Dates are uncertain, but most accounts estimate this was around the year 1130.

He carved out a shelter in the sandstone, hewn with small window-holes and a simple arched doorway. Here he lived and worshipped, dressed in meagre rags.

One day, the Lord of the Manor of Ockbrook and Alvaston happened to discover the baker, known as Cornelious, living in the hermit cave in Depedale, while hunting with his dogs and friends across his land. William FitzRalph took pity on the baker, seeing him living like this, so permitted him to live on his land and granted him the tithe of the mill at Borrowash. His daughter, Maude, and her husband, Geoffrey, continued the legacy of protection and gifts.

The sacred well

An important part of life is always having a good, clean source of drinking water, and such was the case for Cornelious living in those most basic conditions; a spring to collect water was paramount to survival.

And so, perfectly placed, in the dale was a spring which sustained him. In later times, people made the pilgrimage to visit this sacred well, fed from the spring. A sacred well indeed.

The well is said to be on private land, in a garden in Dale Abbey village.

Protected Scheduled Ancient Monument

The cave and its carved cross are now protected as a scheduled ancient monument and remain a small, secretive pilgrimage for those who like history with an element of solitude.

Walking up the steep, leafy steps into the hollowed rock feels like stepping into a medieval reliquary — the stone is cool and the light through the “windows” falls at an angle that belongs to other centuries. A peaceful location where I often pause for a while to enjoy listening to the beautiful bird song, occasionally I have heard the distant sound of a woodpecker, and there is a gentle rustle of wind blowing through the branches of the surrounding beech trees. In the springtime, the hermitage woods light up with a delicate blue hue of bluebells and a carpet of white flowered wild garlic, and the gentle aroma of garlic fills the air.

When stepping inside the hermit cave, the woodland light filters through the windows and gently illuminates the carved cross on the hermit cave wall and the tiny carved out altar on the opposite sandstone wall. I suggest spending time just enjoying the moment and taking in the calm atmosphere here. It feels still, and there’s a cool temperature, most likely due to the nature of the sandstone cave.

Be careful when walking the steps here, especially so after heavy rain or indeed a winter frost. One set of steps that goes to the top of the wood is particularly steep, so be cautious when visiting.

Walking through the Hermitage Woods in Spring, awash with fragrant wild garlic and bluebells.

All Saints: the ancient church and living village worship

Dale Abbey’s parish church (All Saints) has a long history of serving the local community and stands near the abbey ruins. While the abbey’s monastic buildings were largely dismantled after dissolution, the church remained a focal point for villagers — a living thread running from medieval devotion to modern parish life. Strolling from the churchyard towards the abbey ruins, you’ll feel how stitched-together the place is: fragments of the grand and the domestic sit cheek by jowl.

All Saints’ Church in winter

All Saints Church at Dale Abbey has been described as one of England’s most Idiosyncratic churches. I feel this is a very welcoming church where the past meets modern day. There is still a Sunday service here to serve the village community.

The All Saints church is attached to Vergers Farmhouse, which is both a Tudor, grade 1 listed building, and together they are a stunning sight and very photogenic.

The house was once the infirmary of Dale Abbey, with the chapel attached to it. When the sick entered the chapel, they would have used the outside stairs and on to the upper gallery. The church or chapel, as it once was, is only 25 ft by 26 ft, a tiny, cosy place of worship and functional but also filled with history and heritage, one of England’s smallest and oldest parish churches.

Interior photos of the inspiring and historic All Saints’ Church at Dale Abbey.

Inside the church, there are 13th-century wall paintings, 17th-century box pews, and a pulpit of 1634. The nave masonry is Norman and has later additions.

Post dissolution, the infirmary became the Blue Bell Inn, but in later years it became a farmhouse and is now a private home.

Vergers Farm and All Saints’ Church

Ghosts, legends, and woodland whispers

If you believe in ghost stories, Dale Abbey won’t disappoint. Local legend suggests the presence of a melancholy monk or spirit haunting Hermit’s Wood — witness accounts of a shadowy figure seen at dusk, a lingering sorrow that hangs among the trees. The main legend is of a young monk who, reportedly, sadly hung himself in the hermitage woods close to the hermit cave.

There have been many recorded versions of these tales, and the Hermitage’s atmosphere invites them: the mix of ruined stone, ancient pathways, and the hush of beech and ash makes the imagination fertile. Treat these tales as you may — folklore that colours the landscape rather than literal fact, or a haunting — but do go with a readiness to feel small in a place that remembers.

The Mines, Sand Pits and Tram line of Dale Abbey

Hidden among the quiet woodlands and rolling fields of Dale Abbey in Derbyshire lies a lesser-known chapter of the area’s history — one shaped not by monks and hermits, but by miners and labourers. While the ruined arch of Dale Abbey is a familiar sight to walkers and history lovers, the surrounding landscape also tells a story of industry and enterprise. The remains of old sand pits, small-scale mines and even the traces of a narrow-gauge tramway hint at a time when this peaceful valley was alive with the sound of shovels, wagons, and the rumble of machinery.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Dale Abbey and the neighbouring village of Kirk Hallam were part of Derbyshire’s modest but industrious mining scene. Beneath the rural scenery lay rich seams of coal, clay and fine building sand. Small, locally run mines were dotted around the area, often family-operated or employing only a handful of men. These small collieries never rivalled the great pits of Ilkeston or Shipley, but they provided steady work for local people and fuel for nearby farms and cottages.

The sand pits, however, became one of Dale Abbey’s most distinctive industries. The valley’s soft, clean sandstone — part of the Sherwood Sandstone Group — was ideal for glass-making and construction. Companies quarried it for decades, carving out deep pits that are still visible today as woodland hollows and unusual earthworks. The sand was prized for its purity, and some of it was even transported further afield by wagon and, later, by rail connections through the Erewash Valley.

To move the heavy sand and stone, a narrow-gauge tram line was laid, snaking through the woods towards the main transport routes. These small-gauge railways, sometimes only two feet wide, were a common sight in rural industries of the time. At Dale Abbey, the tram line allowed workers to haul sand from the pits down to loading areas more efficiently than horse-drawn carts could manage alone. Small wagons were pushed or pulled along the tracks, at first by hand or horse, and later possibly by small internal combustion engines as technology advanced. Although little of the tram line remains today, its route can still be traced by careful eyes following the embankments, cuttings, and tell-tale ridges in the woodland floor.

The sand pits gradually fell silent by the mid-20th century as large-scale industrial extraction moved elsewhere and the land was reclaimed by nature. Trees and undergrowth have softened the scars of digging, and the paths once trodden by miners and quarry men are now walked by ramblers and nature enthusiasts. Yet, in some corners of the woods, the old industrial heritage still whispers through the landscape — a rusty rail fragment here, an overgrown track bed there, silent reminders of a once-busy working life beneath the Abbey’s shadow.

Today, the legacy of Dale Abbey’s sand pits and tram line adds another fascinating layer to the area’s already rich tapestry of history. From medieval monks to Victorian miners, each generation left its mark, shaping the valley we see now — a place where industry, history, and nature have all played their part in telling the story of this quietly remarkable Derbyshire village.

Little Hay Grange Archaeological Project

Little Hay Grange & the Romano-British building near Dale Abbey

Little Hay Grange (sometimes written Littlehay) is the farm/field just east of Dale Abbey where a local archaeological project in the 1990s uncovered the remains of an Iron Age and Romano-British settlement, including the footings of an aisled building often described in the literature as a Roman barn or villa-type structure. Excavations recorded pottery, a brooch, an Iron Age silver coin and structural features such as stone footings for timber walls and inserted internal rooms, showing occupation and reuse from the Iron Age into the Roman period.

The digs were carried out between the mid-1990s (reports commonly cite 1994–1997) by local teams and archaeological specialists; the site was later back-filled and returned to farmland, so there is now little to see on the ground, though a local information board on the nearby public footpath records the project and its findings. Much of the detailed reporting appears in regional archaeological journals and county reports rather than as a visible visitor attraction.

Why it matters (brief): the Little Hay Grange finds help fill out the picture of rural life around Roman Derbyshire — showing that the area around Dale Abbey was occupied before the medieval abbey and that people were farming, building aisled agricultural structures and living here well before the later medieval landscape was imposed. If you want to see anything in person, follow public footpaths around Ockbrook/Dale Abbey where the interpretation board is sited, but bear in mind the actual excavation trenches have been filled in and remain on private land.

Walking around Dale Abbey — routes, tips, and what to expect

Dale Abbey is modest in scale but richly connected by footpaths. It makes a fine short morning or afternoon walk, or the perfect focus for a longer circular hike that takes in Locko Park, the Erewash Valley, and neighbouring villages.

Practical pointers:

Typical routes & length: Popular loops vary from short 2–4 mile circuits up to 7-mile figure-of-eight walks linking Ockbrook and Dale Abbey or extending to Locko Park. Many route guides and apps list circular trails that pass by the abbey ruins, All Saints' Church, and Hermit’s Wood.

Where to start / parking: There is limited parking near the village; many walkers park in a lay-by or on roadside spaces close to the start of footpaths (some described routes begin from a larger lay-by a short walk out of the village). Several walk descriptions also suggest starting from nearby Ockbrook or Ilkeston if you’re arriving by bus or prefer a longer route. Bring change and expect no guaranteed car park facilities.

The Hermitage access: A clear footpath leads from the village, or as we tend to do is walk from Potato Pit Lane, DE7 4PJ. (Potato Pit Lane is so named because there was a small cavern with a door where potatoes were stored for locals to use).

My favourite short circular walk

Marysia Zipser, Founder of Art Culture Tourism - International and ACT Ambassador, took this walk together on our visit.

From the roadside gate at the lay-by of Potato Pit Lane, proceed towards the Hermitage woods along the lower path, keeping the woodland to your left. Go through the next gateway, where you will find an information point.

You will see the steps leading up to the hermit’s cave almost immediately. Take care on your way up due to weather conditions and the possibility of slippery steps after rain or frost. Enjoy your time taking in the atmosphere, listen to birdsong here and notice the little details of the past. You'll find another information point here too.

Take the steps down and return to the lower pathway. You'll notice that the path leads upwards along a sandstone path.

Continue up and follow it down again to the right, to meet the path leading past Vergers Farmhouse and beside All Saints Church.

Enjoy the journey and see the beautifully preserved church and churchyard. Again, I ask for respect throughout. The church is a charming place and is still used by the local community. Vergers Farm is a privately owned home.

After leaving the driveway, either turn left and explore the village and visit the local Carpenters Arms or take a longer route. There is another fascinating information point at the bottom of the village too, showing points of interest throughout the area.

The shorter route passes by the Abbey ruins archway, the photogenic and inspiring east window. You will notice the signposted public footpath and a little gate after leaving the drive and to your right.

Take a few peaceful moments as you reach the ruins. A serene spot indeed, I find it lovely to be in the moment here, just listening to nature's own music, the rustle of wind, bees buzzing by and if you’re using your imagination, you may feel the quietly spiritual heart of Dale Abbey.

A beautiful old tree near the first stile to your right, before walking across the wildflower meadow keeping on the public footpath heading right till you find the second stile.

Moving onwards, there are three stiles to climb over. One at the end of the field to your right, followed by the second slightly higher stile after following the public footpath to the right again a short way through a wildflower meadow. A beautiful sight in summer.

After this second stile, watch out for a field prone to deep mud in bad weather conditions. Please keep to the path and away from the horses. Adhere to the signage. Climb the third stile and you find yourself back in the first meadow field where we began.

I hope my guidance helps explore the area for a short distance. There are a few useful walking apps that can be used to take you further afield.

Advice, reminders and tips...

Walking up into Hermit’s Wood, steep steps climb to the cave entrance or when walking down the very steep steps from the top woodland path. The cave itself is located on protected ground; please stay on the paths and avoid disturbing the carved features (it’s a scheduled monument).

The coordinates for the hermit’s cave are; 52.942188-1.346494

Underfoot & footwear: Paths can be muddy and steep in places, especially after rain. Sturdy boots are recommended; dogs should be kept under control where paths cross grazing fields.

Facilities: There is a local village pub called The Carpenters Arms and there is a lovely and very popular farmhouse cafe called The Cow Shed which I highly recommend that I have visited with my family for coffee and breakfast.

I also visited The Cow Shed previously with Marysia Zipser; we enjoyed coffee and delicious pancakes at a picnic table outside. Be aware that although the cafe has plentiful indoor seating, it does get very busy at times due to the quality of the food and its popularity.

The Cow Shed details:

No Man's Lane, Dale Abbey, Ilkeston, DE7 4PH

Free limited parking is available nearby.

Why does the place feel so intimate and romantic?

Dale Abbey has none of the grand, manicured showmanship of a major National Trust property — and that’s its charm. The arch of the east window stands alone now, framing fields and sky; to stand within it is to feel part of a ruinous poem. The hermit’s cave is human-scale and intimate; the churchyard is quietly used by the living. The mood here is one of layered time: you can almost hear the rhythm of medieval prayer, the whisper of monks' cloaks, and then the steadier, ordinary present—the bray of a tractor, a dog’s bark, someone pruning a hedgerow. That juxtaposition makes it perfect for slow writing, sketching, photography, or walking where silence is part of the map.

A few respectful dos and don’ts

Do keep to the marked footpaths and gates — many fields are working farmland.

Do treat the Hermitage and abbey ruins with care: they’re protected historical sites. Don’t climb on fragile masonry.

Do wear boots and bring a paper map or an offline route on Komoot/AllTrails; phone signals can be patchy. Don’t light fires or leave litter — small sites like this are cherished by local communities and wildlife.

It is a very green and peaceful place, with gentle meadows, rolling up to the hills that surround it. The Heanor poet, Richard Howitt captured it perfectly:

“O Deepdale! Lovely is thy land, with pasturing herd and flock;

And lovely is thine hermitage

Cut in the solid rock.

A cheerful of healthful life-

A spot of nature's love;

With greenest grass up to the door,

And crowned with trees above.”

~ Richard Howitt (1799 - 1869)

Final thought — how to visit with the heart open

If you go, take time. Bring a notebook, or sketchbook, sit by the tall arch as a breezy frame for the fields, and listen. The Hermitage will reward a slow ascent; the churchyard will accept a quiet thank-you. Walk without the need to tick a list. Dale Abbey is best when you let its small stones and deep woods rearrange your pace: a place to soften the edges of a busy day and to remember that some ruins are not just ends but doorways — places where stories live on, and where visitors become part of the continuing, gentle history.

Janine Moore

Janine Moore is a Nottinghamshire-based writer and blogger with a passion for uncovering the stories hidden within England’s landscapes, heritage sites, and walking experiences. Drawing on years of exploring historic estates, charming towns, and countryside trails, she loves to share her experience of travel, history, and hearty food in a way that’s both informative and inviting.

Living in the heart of Nottinghamshire, Janine is perfectly placed to explore some of England’s most captivating regions. From the romantic ruins and rugged beauty of the Peak District—one of her favourite places to roam—to the legendary Sherwood Forest and the elegant halls of historical properties, she approaches every journey with a storyteller’s curiosity and a photographer’s eye.

Janine also writes for the www.baldhiker.com website on countryside walks, food and heritage subjects. Please read Janine's last article on Byron's favourite walkng spots 26/10/24 https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/post/walking-in-byron-s-favourite-countryside-spots

This article is published by Marysia Zipser, Founder of Art Culture Tourism & ACT Ambassador, Nottingham, UK. https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/blog

Please feel free to write any remarks to Janine in the Comments box below and to share this article via email and social links as you wish. Thank you.

Useful Links:

- Art - Culture - Tourism

- Oct 11, 2025

- 21 min read

Updated: Oct 14, 2025

By Marianne Coxon

11 October 2025

Six years ago I became interested in the Hardwick Hall Noble Women hangings when I started my first role with the National Trust as a Creative Interpreter discussing the meanings behind these wonderful hangings as part of the ‘We are Bess’ project. The crux of the project was to explore the true nature of Bess of Hardwick who had been maligned by her last husband the Earl of Shrewsbury and mainly male writers since. The aims were also to include famous modern women’s experiences of misogyny and draw parallels between both the modern, Elizabethan and ancient women’s experiences. To counter that negativity, the strengths of the women from each age was also explored.

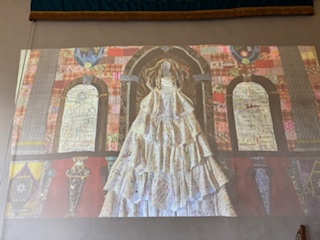

In the early 1570’s Bess of Hardwick commissioned five large wall hangings of noble women from antiquity that she admired for their courage and steadfastness. The hangings were made from materials used for religious observances such as copes and vestments prior to the Reformation and obtained by Bess’s husbands Sir William Cavendish and Sir William St Loe. Today the remaining four hang at Hardwick Hall and you can see these wonderful hangings for yourself during a visit there. Unfortunately the fifth hanging featuring Queen Cleopatra is no longer suitable for display as it has been used to repair the other hangings over the years and only a fragment remains. However, during the month of October this fragment is on display at the hall.

Recently Hardwick Hall launched Material World showcasing the wonderful tapestries, embroideries and wall hangings that were collected firstly by Bess but added to by the Cavendish family over the following years. The Noble Women hangings make up a significant part of this collection because of their uniqueness, their rarity value. Artist Layla Khoo @https://www.laylakhoo.com/ created a brand new Noble Women hanging to replace the lost Cleopatra and the visiting public were asked to add

their personal notable women’s names to the work, women that they admired for varying reasons. This artwork formed part of a research project between the National Trust and the University of Leeds exploring how contemporary art may influence visitors’ engagement with our heritage such as at Hardwick Hall. Those names were embroidered onto the artwork to make the choices a feature that could be viewed by other visitors and enjoyed and appreciated as a whole by all. It was a successful venture and a short film featuring the new work is currently on display at Hardwick Hall.

As part of International Women’s Day earlier this year, I talked about five noble women from the Cavendish family that I admire. These are either descendants of Bess or married into the family. One of the women had a tragic life, full of disappointment, others just railed against the misogynistic society of the time in which they lived, but nevertheless stood their ground and lived their lives to the full. They had several things in common however, personal courage, intelligence, determination and loyalty to their loved ones. They also displayed similar traits to the noble women from antiquity in greater or lesser degrees and I have endeavoured to forge those character links between the ancient and more modern women. I trust you will find them all as interesting and inspiring as I do.

The noble women from antiquity featured in the wall hangings are as follows:

Penelope, faithful wife of Ulysses in Roman mythology (Odysseus in Greek mythology). She was queen of Ithaca and mother of Telemachus in Homer’s Odyssey. Penelope remained faithful to her

Centre - Penelope greeting Ulysses on his return home from war after a long absence of 20 years. Portrayed in a Brussels tapestry in the High Great Chamber, formerly the Presence Chamber.

absent husband who was away fighting in the Trojan wars for 20 years. During Ulysses’ long absence Penelope was pressured by potential suitors into remarriage but kept them at bay with promises to consider their proposals after completion of a funeral shroud that she was weaving for her father in law, Laertes. Every night Penelope would unpick her work and so never completed her task. After 20 years absence, Ulysses returned to his faithful wife who had demonstrated faithfulness, intelligence, strength and endurance.

Penelope appears to have been a favourite of Bess as her story was also told in the Brussels tapestries on display in the High Great Chamber at Hardwick Hall.

Lucretia was the wife of a Roman nobleman Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus who lived during the time that Rome was ruled by a monarch. Lucretia welcomed the king’s son Sextus Tarquinius who had called on her unexpectedly at their home whilst her husband was away. The prince repaid her

generosity by raping her. Upon her husband’s return, Lucretia confessed to the rape and then stabbed herself to death because of the dishonour brought to her family.

This incident led to the end of the royal succession and a Roman republic was formed in its place. Lucretia sacrificed herself for the honour of her family after enduring terrible sexual violence. Later, Lucretia was portrayed as an honourable wife and a role model for Roman womanhood.

Both of the above are on display in the Exhibition rooms at Hardwick Halls

Artemisia II of Caria was the sister and wife of King Mausolus who upon the death of her beloved husband had his body cremated and his ashes dissolved in a goblet of wine which she drank to make her own body a living tomb for her husband. By this act Artemisia became a symbol of noble and chaste widowhood.

Zenobia queen of Palmyra in Syria - a Roman colony - was the widow of Odaenathus who had been assassinated. Zenobia made herself ruler of Palmyra and regent for her young son

Vaballathus was head of the Palmyrene army in the years 267/8 to 272 CE. As ruler she revolted against Rome and expanded the Palmyrene empire to include Egypt and considerable parts of Asia Minor. She was eventually subjugated by Emperor Aurelian. Zenobia is thought to have descended from Cleopatra Egypt’s ruler and embodies, courage, military leadership, strategic thinking and single-mindedness - a skill set that she shared with Cleopatra.

These are displayed in the Chapel landing at Hardwick Hall.

Cleopatra VII 69/70 BCE to 30 BCE an Egyptian queen of the Ptolemaic dynasty who rose to power on the death of her father Ptolemy XII in 51 BC and ruled alongside her brother Ptolemy XIII. A courageous, intelligent and well educated leader like her descendant Zenobia, she nevertheless was the last active ruler of ancient Egypt. She famously became the mistress of two powerful Roman men, firstly Julius Caesar then later Mark Anthony, but these relationships are believed to be more politically and strategically motivated than romantic attachments as they helped her maintain her grip on the throne that was threatened by her co-ruling brother.

At time of publication, October 2025, a fragment of the Cleopatra wall hanging is displayed (above left) in the Exhibition rooms at Hardwick Hall. Right - Posthumous painted portrait of Cleopatra VII of Egypt from Herculaneum, Italy.

The following are women from the Cavendish family, either descended directly from Bess of Hardwick or married into the family. What they all share is nobility in various forms, courage, resourcefulness, integrity, determination, loyalty and intelligence. I have linked their characters to those of the noble women from ancient history that Bess so admired and celebrated.

Evelyn Cavendish, 9th Dowager Duchess of Devonshire 1870-1960

Left: Detail from a portrait of Lady Evelyn Cavendish, John Singer Sargent (1902). Chatsworth House.

Centre: Photograph of the Duchess of Devonshire , George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress , Washington D.C.

Right: Evelyn Fitzmaurice, Duchess of Devonshire (1870-1960), by Edward Irvine Halliday ARA (Liverpool 1902 - 1984).

@National Trust Hardwick Hall

Evelyn became Duchess in 1908, her marriage to the Duke produced two sons and five daughters. Tragedy struck when her husband Victor suffered a major stoke in 1925 and her once happy ordered life became challenging. Victor, once so jovial, became difficult and hostile to Evelyn. Evelyn gradually took over the management of his affairs. On his death in 1938, Evelyn moved to Hardwick Hall where she spent her final years conserving and repairing the collection of tapestries, embroideries and the Noble Women Hangings, saving them for the future. Due to the unexpected death of Evelyn’s son Edward the 10th Duke, the family were faced with 2 sets of death duties to pay. To settle this debt, Hardwick Hall was handed over to the National Trust in 1959 by the Cavendish family. The Trust and nation owes the Duchess much for her dedicated care of the collection.

Evelyn was born into Victorian society where duty, courage and personal sacrifice for that duty was the societal norm of the day. Evelyn did not lack courage, nor did she shirk her duty when faced with a sick and hostile husband, she took the reins and ran the estate and his business affairs. Evelyn stood by her family throughout her life during a time of much social change and two world wars. Even her conservation of the tapestries and embroideries was a loving duty for her family. That is why I have placed her amongst my collection of noble women.

With which of the noble women of antiquity do I associate Duchess Evelyn? Firstly Penelope for her loyalty and steadfastness in the face of uncertainty but also Queen Zenobia who took the reins after the death of her husband and made herself an effective head of the Palmyrene army and created an empire of her own. I will add in Artemisia as well as her whole life was one of duty, loyalty to her husband and personal sacrifice.

Margaret Cavendish Duchess of Newcastle 1623-1673

Margaret Cavendish nee Lucas born in 1623 became the second wife of William Cavendish, a Royalist Commander whose love of pleasurable pursuits such as dressage were of considerable importance to him. Margaret was a writer, poet and essayist with a keen sense of justice and published her own works under her own name. Her published works included a collection of poems called Poems and Fancies published around 1651 and later a science fiction work called Blazing World. These were met with mixed feelings but many praised her work for brilliance and freedom of thought. Her personal experience of the abuses of wardship when her own brother’s wardship was sold off after their father’s death was protested against in her writings. She believed in the rights of women and education for females, all against the accepted societal norms for the role of women in 17th century England. Margaret learned about Philosophy from her brother in law Charles and was the first woman to attend the Royal Society in 1667, an event witnessed and recorded by Samuel Pepys. Ridiculed for her forward-thinking ideas and her individual style of dress, Margaret was a woman ahead of her time.

Margaret Lucas, 1st Duchess of Newcastle, Peter Lely, 1665. © Harley Foundation, The Portland Collection.

Please read Hannah Marple's article Decoding historical costume: Meet the Cavendishes here https://harleyfoundation.org.uk/explore/entry/historical-costume/

Margaret was an accomplished and intelligent woman very much ahead of her time, and possibly born into the wrong time too. Her views and actions were considered outlandish at the time when most women were subservient. She intrigues me and has my vote for being amongst the noble women. I would love to have met her. I think she would have been great fun!

So which noble woman from antiquity do I associate Margaret with? Well for myself she embodies the adventurous spirit of Cleopatra and the loyalty and devotion of Penelope to her spouse. In fact, I understand from a biography of Lady Margaret Cavendish by Katie Whittaker that Margaret disapproved of Cleopatra, possibly for her liaisons with Caesar and Anthony but liked and approved of Penelope for her loyalty to Ulysses.

Miniature of Margaret Cavendish from Luminarium.

Collection unknown.. Wikipedia Commons.

Christian Cavendish nee Bruce, 2nd Countess of Devonshire 1590-1675

An unwanted wife to Bess’s grandson and heir of the 1st Earl - Christian eventually bore young William four children. Christian was intelligent, determined, loyal and capable and this was proved when the Earl died in 1628 aged 38 deep in debt shortly after succeeding to the title. Christian spent years successfully fighting off lawsuits filed by his many creditors and managed to keep the Cavendish estate intact so it could be settled on her eldest son, William, the 3rd Earl. A staunch supporter of the Royalist Cause tragedy struck again in 1643 when she lost another son Charles during the Civil War. Her youngest son Henry had died in 1620. Nevertheless she successfully negotiated good marriages for her remaining children and lived to be a respected person in her own right.

Christian (centre) with son William (left), 3rd Earl of Devonshire., Charles (centre right), and daughter Ann.

Painting by Daniel Mytens. c1629. Chatsworth House. Right: Detail

Despite being a staunch Royalist, Christian became well connected to the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, because his daughter, Frances Cromwell, married one of Christian’s Rich grandchildren (children of Christian’s daughter Ann who married Robert Rich, 3rd Earl of Warwick). Christian also attended Cromwell’s Court.

For Christian to turn an unpromising marriage around where her husband would rather spend his time pursuing his own interests and become a wife that produced four children and remained loyal to her husband was no mean feat. She also saved the family’s good name and negotiated a good relationship with a man who had the potential to be her sworn enemy and a dangerous one too - Oliver Cromwell. Christian achieved all this by her sheer determination, emotional intelligence and skill.

I admire Christian for her courage and endurance in the face of so many challenges, so she gets my vote as a noble woman.

Christian’s courage, loyalty, intelligence and endurance links strongly with Zenobia, Penelope and to a good degree, and Cleopatra, who survived by making alliances with would be enemies. So hats off to Countess Christian for her bravery, tenacity and sheer determination to survive and thrive.

Arbella Stuart 1575-1615

Left: Lady Arbella Stuart at age of 13 years 6 months. English School circa 1588/1589. @National Trust Hardwick Hall

Centre: Detail Right: Detail from Hardwick Hall Portrait. Sarah Gristwood: Arbella. England's Lost Queen. 2003:, Bantam Books

Arbella Stuart was Bess’s granddaughter and had the bloodline of the Tudor and Stuart families in her veins; in fact, Arbella’s great grandmother was Margaret Tudor widow of James IV of Scotland so Arbella was privileged with a strong claim to the English throne. She was niece to Mary Queen of Scots and first cousin to James VI of Scotland. As a child, Arbella’s future looked bright and full of promise. Intelligent and highly educated, Arbella was brought up as a Princess of the Blood by her grandmother after the death of both her parents. Negotiations were entered into for advantageous marriages but none ever came to fruition. Queen Elizabeth, although appearing to hint that Arbella would succeed her as queen never actually seriously furthered Arbella’s chances, but was happy to use the young woman as a political pawn offering her in marriage to prospective grooms using Arbella’s possible succession to the throne as a sweetener. Time marched on and nothing changed, no husband, no children, no glittering future, instead Arbella lived mostly with her grandmother at Hardwick and began to feel trapped and thoroughly resentful at being treated like a child. Finally Arbella tried to arrange a marriage for herself in the early 1600’s, however being of royal blood, permission to marry had to be sought from the monarch which she failed to do. Her chosen groom was Edward Seymour and any children of such a union would have a strong claim to the throne of England. When the plans were discovered Queen Elizabeth was angered and Sir Henry Brouncker was despatched by her ministers to Hardwick Hall to interview Arbella about her discovered plans. During the interview Arbella became visibly distressed and tried to pretend that her unknown lover was James VI of Scotland, which in all probability, was to throw Brouncker off the scent. Finally in March 1603 Queen Elizabeth died and Arbella’s cousin James was crowned.

Bess died in 1608 and Arbella arranged to marry again, this time to William Seymour and again without the monarch’s consent. Her groom was 6th in line to the throne and known as Lord Beauchamp. He eventually became 2nd Duke of Somerset but this was after Arbella’s death.

Because of her unwise marriage that threatened the new monarch James, the couple were separated and William was put in the Tower. Arbella was scheduled to be placed in the care of the Bishop of Durham but feigned illness en route to Durham and escaped dressed as a man taking a ship to France where the couple planned to reunite. William’s escape was delayed and he missed the rendezvous with his wife. Arbella was caught just outside Calais, but William following on, evaded capture. After Arbella’s

Lady Arbella Stuart. 1605. by Robert Peake the elder. (1551-1619) .

Oil on panel. Scottish National Portrait Gallery, National Galleries of Scotland

attempt to escape to France, James eventually imprisoned her in the Tower where she died just shy of 40. Her husband William Seymour managed to get to France but stayed in hiding abroad leaving Arbella to face her imprisonment alone. Arbella’s life was one once full of promise that dissolved into disappointment and despair. All her efforts to improve life for herself were cruelly thwarted, and by marrying without permission she exchanged one prison for another. Arbella’s life should have been happy and fulfilled, she was an intelligent, educated and an able young woman but was a pawn in a power game she could never win. Had she been alive today, I believe that she would have carved a great future for herself. I admire her for her strength and endurance despite the obstacles that were placed in her path. Arbella’s mental health problems may well just be due to frustration and deep depression, but scholars have estimated that her recorded symptoms point to a likely diagnosis of porphyria.

Arbella never gave up trying to be her own person despite all her setbacks and frankly cruel treatment by those in power and betrayal by her husband - that is the reason I regard Lady Arbella Stuart to be a noble woman.

So to the gritty question. ‘With which noble woman from antiquity do I align Lady Arbella?’ For myself, undoubtedly Lucretia who, having been cruelly betrayed and violated by Sextus Tarquinius, felt honour bound to end her blighted life.

I feel it has to be said that Arbella herself was cruelly betrayed by Elizabeth I who used her as a pawn in her power games uncaring about the young girl’s own feelings or welfare. Some others also could be accused of using Lady Arbella Stuart for their own ends. Bess to a certain extent because of her own ambitions and Henry Cavendish, Bess’s oldest son used Arbella’s plight to get back at his mother from whom he was estranged. James I who took away her title, Countess of Lennox, and gave it away to one of his favourites Esme Stuart, he kept her short of money and on a very tight leash to control her but who also took away her liberty and any chance of happiness with her husband William Seymour.

Lady Arbella Stuart. Cabinet miniature by Nicholas Hilliard, 1592. Private Collection. Wikipedia Commons.

Lastly it is thought that King James was behind the theft of the Lennox jewels left to young Arbella on the death of her grandmother Lady Margaret Douglas. The jewels were lost in a robbery whilst they were en route to Lady Arbella. A singularly spiteful act of which the king was suspected being behind.

Bess of Hardwick c.1521-1608

Born in the early 1520’s, and known as Bess within her family. Elizabeth Hardwick’s young life was turned upside down when her father died in 1528 and her brother’s wardship was sold off as he was still a minor, plunging the family into financial hardship. Bess watched as her mother struggled to support her family and was aware that the family estate they once owned outright was now in the hands of an unwanted stranger. She noted the humiliation the situation caused her mother as she negotiated renting a portion of her late husband’s lands from the Court of Wards so that she and her family could have a better chance of surviving. This early experience of the harshness of Tudor life faced by those without financial means will have strengthened her resolve to never be humiliated or bested by those with power over her. When Bess’s first husband Robert Barley died after 18 months of marriage in 1544, Bess was refused her Dower payments from her late husband’s estate. Bess did not take no for an answer as she was entitled by law to her Dower payment. Instead she took her case to the Court of Common Pleas, where she was unsuccessful. Not to be deterred she then approached The Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Wriothesley, who served in the Court of Chancery and Bess continued fighting until an agreement was reached.

Top left: Bess of Hardwick portrait holding gloves painted 1560-69, it was when she was married to Sir William St Loe, Captain of the Guard for Queen Elizabeth and Chief Butler of England, her third husband. The portrait displays her as a powerful high status woman because she is richly dressed and facing towards the viewers' right a stance normally preserved for male sitters. .Painted in the style of Hans Epworth. Hardwick Hall Collection. Oil on panel. From the National Trust website.

Top right: Bess of Hardwick as a widow for the final time (with several ropes of pearls). Probably Rowland Lockey circa 1565-1616 London. Portrait in the Portland Collection, Harley Foundation, Welbeck..

Bottom left: Detail of above Bottom right: Portrait showing Bess as the 'Countess of Shroesbury' painted circa 1580. Oil on canvas English School, sitter facing towards the viewers' right as above. Hardwick Hall, The Devonshire Collection (acquired through the National Land Fund and transferred to National Trust in 1959.)

Bess had many struggles in her life, but her earliest when she was a very young woman shaped and strengthened her for her future especially when dealing with her last husband who gradually changed from a loving man to one who loathed her and meant her harm. Bess married four times in total which was not unusual for that period. Widows/widowers were expected by society to

remarry fairly quickly in those times. Bess birthed eight children all together with her second husband Sir William Cavendish and six of them survived to adulthood. Three sons and three daughters, these all made good marriages but sadly not always happy marriages.

Sir William Cavendish (1505 – 25 October 1557), English courtier, second husband of Bess of Hardwick. c.1547. @National Trust 2008, Hardwick Hall

William Cavendish, Bess’s second son and later her successor to her estate, became Baron Hardwick and later the Earl of Devonshire. Henry, Bess’s eldest son’s marriage, was childless and unhappy and resulted in an estrangement from his mother. Frances Cavendish married Sir Henry Pierrepont whose descendants became the Dukes of Kingston, Mary Cavendish married Gilbert Talbot the future Earl of Shrewsbury and the final daughter Elizabeth married the Earl of Lennox and their child, Lady Arbella Stuart had a strong claim to the English throne after Elizabeth I.

Charles Cavendish Bess’s youngest son’s descendants became the Dukes of Newcastle, later Bentinck and Portland. In the 20th century our present monarch King Charles III was born - another descendant of Bess of Hardwick. His great grandmother was Lady Cecelia Nina Cavendish Bentinck who married a Scottish nobleman and became Lady Cecilia Nina Bowes-Lyon the Countess of Strathmore and Kinghorne.

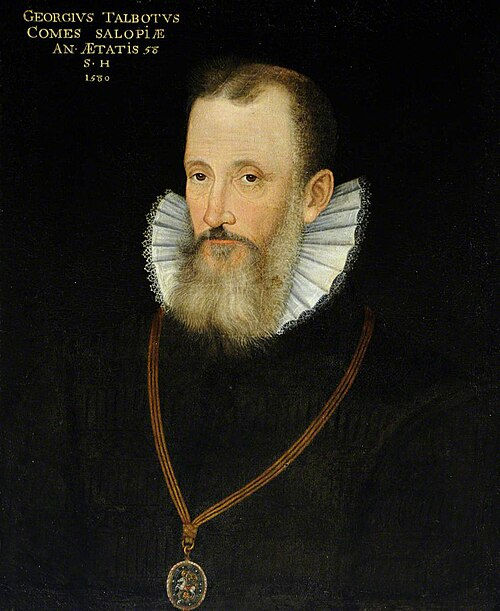

Bess’s final and longest marriage was to the Earl of Shrewsbury, George Talbot, which elevated her to the nobility with the title of Countess of Shrewsbury. This marriage was eventually blighted in part by the strain of becoming the keeper of Mary Queen of Scots for fifteen years only eighteen months into their marriage.

The Earl was one of the wealthiest men in England and upon his death in 1590 Bess inherited one third of the income of his estate as her widow’s dower making her the second richest woman in England, bar the monarch. Bess lived on until 1608, dying peacefully at Hardwick New Hall the architectural jewel designed for her by Robert Smythson.

Lockey, Rowland; George Talbot (1528-1590), 6th Earl of Shrewsbury; @National Trust, Hardwick Hall;

Many historians, even some today, dismiss Bess as a ruthless, money grabbing operator determined to climb as high as possible in Elizabethan society at the expense of other people’s interests. However, recent studies, including those of Bess’s personal letters by Dr Emma Turnbull have found a different Bess, one that cared for her family, her husbands and looked after her servants, giving them gifts when they married. The rehabilitation of Bess of Hardwick’s reputation was at the core of the ‘We are Bess’ programme from 2018 and continued in 2019 when I joined the team at Hardwick Hall. This was part of an initiative between the National Trust and the historian Professor Suzannah Lipscomb. Also involved was Polly Schomberg, Creative Director and Creative Producer for the exhibition itself.

It is also believed that the undermining of her reputation was mainly from her estranged last husband George Talbot but also the sibling of her third husband William St Loe who was disinherited by his brother William’s Will. Why was he disinherited? William’s brother Edward had a history of nefarious deeds including allegations of attempted murder against his older brother, Bess and other people and likely because of this behaviour had also been originally disinherited by their father John. Why the alleged attempted murders? William himself had no children of his own so Edward expected to benefit from the family estate after his brother’s death, his marriage to Bess changed that. Therefore, William St Loe leaving everything to Bess upon his death was to protect her from his brother Edward’s schemes.

Sir William St Loe

Unknown author. Design from the Almain Armourers' Album, Royal Armouries, Greenwich, compiled between 1557 and 1587, showing a design for an armour for Sir William Sentlo (St Loe). Wikipedia Commons

So why choose Bess of Hardwick as an example of a noble woman? For myself, it is her sheer determination to not only survive the difficulties that arose throughout her years, but to learn from her experiences and make a success of her life and those are the prime reasons I have chosen this lady. Also, she was the woman that commissioned the original Noble Women hangings so I feel it right and just to include her.

Lastly with whom do I equate the great Dowager Countess of Shrewsbury known as Bess of Hardwick? Well firstly, Penelope for her loyalty to her husbands and her family in particular. Zenobia for her business acumen, and ability to run her houses and her family. Cleopatra for her intelligence and charm. Artemisia for her loyalty to her final husband, the Earl of Shrewsbury despite his many abuses when the marriage floundered. Finally, Lucretia for her humiliation and fear when one July night in 1584 the Earl broke into Chatsworth whilst she was sheltering there with her son William Cavendish. The Earl was backed up by forty armed men with the sole intent of causing as much damage to Chatsworth as possible. Bess had a lifetime interest in Chatsworth and it was entailed to her son Henry.

Towards the end of the Earl’s life he took up with a mistress, Eleanor Britton, his housekeeper, who along with her nephew, stripped the Earl’s houses of as much treasure as they could get away with. This was upon the death of the Earl. Bess tried to recover what was pilfered but only managed to rescue some of the stolen items.

So what links all these women apart from their familial ties? I say, their intelligence, loyalty, and bravery to be the women they were in a world made for and by men. I also include the fact that often their husbands proved to be less than ideal life partners.

Before I conclude, I would like to add a note about the much disputed birth date of Bess of Hardwick. No birth or baptismal records for Elizabeth Hardwick (Bess) have been found and various suggestions have been put forward for this event. The dates range from 1520 during the later Victoria/Edwardian period to the more recent estimation of 1527, and this later date seems to be the currently accepted one. However, clues exist that dispute this later date. Research carried out by

historian Terry Kilburn and recorded in his remarkable book ‘Bess of Hardwick Myths and Realities’ have shed light on the evidence that points to Elizabeth Hardwick being born circa 1521/2. Other historians share the belief that the early 1520’s was the far more likely timescale, these are Philip Riden and Dudley Fowkes in their book ‘Hardwick a great house and its estate’.

Terry Kilburn’s research has concluded that according to Common Law and Canon Law both males and females came of age at 21 years during the time Bess lived. Females, whether spinsters or widows could not be Sole Plaintiffs under the age of 21. When Elizabeth Barley nee Hardwick presented her claim for Dower payment to the Court of Common Pleas in 1545, she was a Sole Plaintiff. If Widow Barley had been under 21 then she would have been represented by her Guardians Henry Marmion and John Leake and the records would have shown that. Terry makes the further assertion that all the Derbyshire families of which Bess was a member, had long established links through intermarriage and business dealings and Elizabeth Barley would not have been a stranger to any of them, nor, likewise her age. Terry presents further evidence from a letter written by Gilbert Talbot to Robert Cecil on 20th November 1604 complaining of his ‘unkind mother in law’ who was then around 84 years of age, this letter cements the evidence still further.

Bess wrote to the Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Wriothesley in 1546 to have her case heard at Chancery. She stated in her letter that she had married Robert Barley when they were both ‘of tender years’. However, marriages during that period were in three parts, the espousal in which the couple were considered as being married, the wedding ceremony and the consummation which was carried out in front of witnesses. Terry Kilburn believes that Bess and Robert were espoused in 1536 when Bess was around 15 years old and concludes that this is why more recent biographers may have experienced scepticism over Bess’s birth date as they confused espousal with the actual marriage ceremony which was, of course, 1543. This takes the birth date back to 1520/21.

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. I hope you found it interesting.

I look forward to welcoming you to Hardwick Hall.

Marianne Coxon

Guide,

Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire

My sincere thanks to Paul Gliddon for introducing me to the work of Terry Kilburn.

Post Script from Marysia Zipser, Founder of Art Culture Tourism - International

“What a glorious tour recently of Hardwick Hall with Marianne who guided me around talking in detail about Bess of Hardwick, her husbands, her family, the Hall and Gardens. Please do go visit and experience their 'Material World' exhibition. The tour is truly an experience you will never forget. Thank you so much Marianne, I really enjoyed it and learned so much. Below are a few exterior photos I took of the day.”

https://www.tourist.me.uk/derbyshire-tourist-information https://harleyfoundation.org.uk/ and The Portland Collection,

Further ACT articles relating to the Cavendishes published 2023 https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/post/harley-foundation-welbeck-nottinghamshire

https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/post/the-royal-horse-of-england-equestrian-show-at-bolsover-castle and 2025 https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/post/the-gorgeous-nothings-at-chatsworth-house

References/Bibliography

Margaret (Lucas) Cavendish Duchess of Newcastle (1623 - 1673) by Ron Cooley et al

(Ron Cooley, Ron and Brecken Hancock, Kristen Kenyon, Annette Lapointe, Joan Morrison, Barbara Palmer, Lawrene Toews). As One Phoenix: Four Seventeenth Century Women Poets. University of Saskatchewan 1998

Bess of Hardwick an Elizabethan Tycoon by Wyn Derbyshire. Spiramus Press, London 2022..

Arbella Stuart A Rival to the Queen by David N Durant. Book Club Associates, London 1978

Bess of Hardwick Portrait of an Elizabethan Dynast by David N Durant. Peter Owen Publishers, 1978.

Arbella England’s Lost Queen by Sarah Gristwood. Transworld Publishers, 2003. A part of the Penguin Random House group of companies.

Hardwick a great house and its estate by Philip Riden and Dudley Fowkes. Copywrite University of London, 2009. Chapter 1 Hardwick and its Owners. Chapter 2 The Making of a Great Estate - page 18.

Phillimore & Co. Limited, West Sussex, England

Bess of Hardwick Myths and Realities by Terry Kilburn. Austin Macauley Publishers Limited, 2024.

Chapter 5 - Matters of Birth and Death. My Bess: A Woman of her Time

Mad Madge Margaret Duchess of Newcastle. Royalist Writer and Romantic by Katie Whitaker. Vintage Books, 2002

Tudor Times: We are Bess - A Photography Exhibition. 6.10.2018.

This article is published by Marysia Zipser, Founder of Art Culture Tourism & ACT Ambassador, Nottingham, UK. https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/blog

Please feel free to write any remarks or questions in the Comments box below and to share this article via email and social link icons as you wish. Thank you.

- Art - Culture - Tourism

- Oct 9, 2025

- 3 min read

By Marysia Zipser

9th October 2025

Photography and videos by Tony Fisher RPS, Teresa Cullen, Jeanie Barton and Marysia Zipser

On Sunday afternoon, 5th October, Marysia Zipser, Founder of Art Culture Tourism - International & ACT Ambassador, hosted an Open House Autumn Gathering at her Beeston home, gallery and garden for artists, writers, photographers, film makers, performers, local councillors, ACT Advisors, university academics & mature students, Notts wildlife enthusiasts, heritage/history/design and museum experts. All valued friends from our Beeston & Nottingham/shire communities…plus cat!

Marysia was honoured with the presence of Broxtowe Mayor Councillor Bob Bullock who came with Broxtowe Alliance councillors Milan Radulovic and Teresa Cullen, joined by Nottingham City councillor Pavlos Kotsonis, and Broxtowe’s Polish C-City delegation visitors from Grudziądz, Ewelina Dąbrowska, with singer Marysia Trętkiewicz and Tomasz Gust playing some Polish songs. More music was performed by Beeston singer Jeanie Barton, all adding a magical accompaniment to the occasion. See header photo by Teresa Cullen.

Cllr Teresa Cullen said, “A big thank you to local community champion Marysia Zipser who invited our Councillors and members of Broxtowe Borough Council C-City delegation including our Polish colleagues to her open house. Tomaz and Marysia played some Polish songs which were a lovely touch. We were glad to be part of this Autumn gathering. Our Polish guests really appreciated it all, it was a lovely afternoon.”

Delicious Italian appetisers were provided by Marco di Blasi, owner and manager of Beeston’s authentic Italian L’Oliva Trattoria. So many compliments were received on the catering side!

Jeanie Barton, ACT Advisor, added, “It was great to perform at Marysia’s for her autumn gathering, a lovely, familial atmosphere. In all a busy weekend, having played the day before 3 times at the 15th annual Beeston Oxjam music festival, which featured 12 hours of live music, 20 venues and over 150 different bands and artists! It was also wonderful for our C-City Polish delegation members to perform there at the Beeston Social - it was marvellous that they came the next day to Marysia’s to complete their spirited Polish journey.”

Jeanie singing...

Marysia read out personal messages from visual artist, journalist, author, Roberto Alborghetti (of Ghost Bus project fame) in Bergamo and ACT Advisor in Ravenna, Patrizia Poggi, who both couldn't be with us on this occasion.

Pam Miller, Fine Artist, said, “Thank you for the invite to such a lovely autumn gathering, Marysia. Great to make new friends and reconnect with old ones. Lovely that ‘The sun had its hat on’ for part of the time. I really enjoyed the singing, courtesy of Jeanie Barton Music and other musicians and the food was gorgeous - Please thank Marco Di Blasi for me, also, catering for the vegan guests (including myself).”

Sasha Prince, Cafe Culture correspondent, The Beestonian magazine, added, “Thank you for the invite, Marysia. It was great meeting such lovely people and having wonderful conversations.”

This song was the icing on the cake for Marysia Zipser sung by Marysia T accompanied by Tomaz Thanks so much!! The song was always sung by her father Mietek Zipser (from Lwow now Lviv) with family & friends whenever there was a celebration in Nottingham. The song is called Tango łyczakowskie.

Dawn Lindson, Nottingham Trent Univ mature student & past ACT volunteer, said, “Lovely to catch up again with you, friends and with ACT developments.”

Pavlos Kotsonis, Nottingham City Councillor for Lenton & Wollaton East, stated, “It was a lovely day and occasion, thank you Marysia! Please keep organising gatherings like this and building international collaborations. Everyone benefits from your efforts.”

John Currie, director of Beeston Film Festival, said, “Many thanks for inviting us, Marysia! We had a fab time! You are an incredible host!”

Marysia concluded, “It was a truly beautiful day and everyone really enjoyed themselves. It’s lovely to appreciate our local community friends in this way by personally hosting once in a while and giving back for all their support. Our ACT Blog is now a popular media platform as we publish regular articles by local, national and international writers who are keen to contribute. I’m also available to give, on request, introductions and ACT talks at Beeston and Nottingham/shire events.”

Please feel free to write any words in the Comments box below and to share this article via email and social link icons as you wish. Thank you.

Marysia Zipser