- Janine Moore

- Feb 6

- 9 min read

Updated: 6 days ago

By Roland “Roly” Keates

Derbyshire

6th February 2026

Winchester Cathedral is one of those rare places where time doesn’t simply pass; it pools. Light doesn’t just fall here; it lingers. It drifts through the vast perpendicular nave as though it has learned the building’s own grammar: long, measured, and precise. You walk in from the bustle of the High Street, the modern chatter and footsteps fading behind you, and everything slows. The echo softens, the air cools, and a hush gathers under vaults that have held the prayers and breath of nearly a thousand years.

The first thing a photographer feels is not the urge to take pictures but to listen to them. Winchester teaches you that photography here is less about capturing and more about receiving. The cathedral gives you line, rhythm, texture, and story; your task is to translate them into a visual language that feels worthy of the place. Every arch, every pier, every shaft of filtered light seems to hold a memory. You begin to realise that your camera is less a machine for recording than a vessel for attention.

Arriving for the Light, Staying for the Quiet

The rhythm of this cathedral is the rhythm of light. To photograph Winchester well, you must learn to move with its hours. The best times to enter are early morning and late afternoon, when the light itself seems contemplative. In the morning, as the great doors open and the first visitors step inside, side light grazes the pillars and reveals the chisel marks left by masons long gone. The air is often still, and dust motes rise and fall like tiny constellations, drifting through the quiet hum of preparation as volunteers light candles or adjust the hymn boards.

By late afternoon, the light has changed entirely. The nave softens; the glass deepens. Gold and rose colours bleed through the medieval and Victorian windows, brushing the limestone and Purbeck marble with a gentle warmth. The floor, polished by centuries of feet, catches those tones and sends them back up in faint reflections. Outside, the flint and stone of the west front gleam pale against the lowering sky. And if the weather turns overcast, rejoice. Soft cloud is the cathedral photographer’s best friend, a giant natural diffuser that reveals detail without glare.

You soon learn that cathedrals reward patience. Rushing will only yield postcards; lingering will yield revelation. Bring a quiet camera, something unobtrusive, and resist the temptation to fire off dozens of shots. Find your composition and breathe with it. Many cathedrals restrict the use of tripods, so hand-held steadiness becomes an art in itself: a slow exhale, a steady hand braced against a pier, ISO raised just enough to respect the shadows. This is not a place for bright intrusion, but for gentle observation.

Before you lift the lens, stand still. Let your eyes adjust. You’ll begin to see the rhythm of movement around you, the soft passing of a verger, the flick of a bird through the clerestory, the shape of silence itself.

Composing with the Building’s Music

Winchester is a symphony of verticals and vanishing lines. The eye is drawn forward by the long, unbroken procession of arches, each bay echoing the next in perfect Perpendicular order. To stand at the centre of the nave is to feel the pull of centuries, a visual gravity that carries you toward the high altar and beyond.

Photographically, this is the cathedral’s great challenge, and its greatest gift. Line, proportion, and rhythm are everywhere, but they must be handled with sensitivity. Stand dead centre and allow the repeating arches to create their own music. A single human figure, placed small within that immensity, becomes not a distraction but a key, a measure of scale, a reminder of the human heartbeat within the stone. Shoot at a moderate aperture, such as f/4 or f/5.6, to maintain sufficient sharpness for rhythm while allowing the distant arches to fade into a gentle blur.

Then step aside. Move into a side aisle and break the symmetry. Cathedrals, like music, are richer for their counterpoint. Use a pier or column close to the lens as an anchor, and let the aisle drift into shadow. The result is intimacy within grandeur, the sense of being alone yet surrounded by time. These quiet perspectives reveal the building's personality, the smaller rhythms that play between the great chords of the nave.

If you shoot a sequence of images, hold the same horizon line across each frame. The eye will then read them like musical notation, a visual cadence of bays and piers that echoes the building’s design. Winchester rewards photographers who think in tempo as much as in exposure.

Texture is Truth

Walk close to the stone and it begins to speak. Winchester’s fabric is layered with centuries: the heavy Norman masonry of the crypt, the lighter Gothic refinements above, the patient work of restorers and stonemasons who continue the tradition today. Texture is the cathedral’s memory.

Look down. The thresholds at the west end are worn into shallow hollows, each step shaped by countless soles. Photograph them low and at an angle so that the light skims the surface, the relief will come alive, each worn edge glinting like bone polished by time.

Move along the choir stalls and study the misericords, the carved wooden supports once used by choristers during long services. They are often whimsical, sometimes grotesque, always human. If photography is permitted, capture them gently, without flash, letting their patina remain intact.

Then turn to the stained glass. Expose for the highlights to preserve the colour. Let the surrounding stone fall into darkness; it will frame the glass more truthfully than any artificial brightening. The lead lines form a calligraphy of faith and craft. Photograph them closely, then step back for a contextual shot of the entire window.

The dialogue between near and far, between the mark of the maker and the sweep of the design, is the cathedral’s own.

Portraits of Place

A cathedral is never only architecture. It is a living theatre of devotion, work, and wonder. People belong in the frame. A photograph without life is only half the story.

Seek out the human moments: a volunteer lighting a candle, a verger arranging flowers, a visitor resting in the pews with eyes closed in thought. Approach quietly and respectfully. Ask permission where needed. The goal is not to stage but to witness.

Use the geometry of the building as your stage set. A figure beneath a clerestory window can be gently crowned by light; a visitor framed between two pillars becomes a modern pilgrim. In these moments, Winchester’s scale becomes human again. The vast stone vaults are softened by presence, by breath, movement, and the simple grace of someone standing still.

If you’re fortunate, you might hear the choir rehearsing. The sound alone changes the air. Capture it if you can, not in a literal image, but in a mood. The faces of the singers, the lift of the music stands, the soft gleam of brass and wood, these are the fleeting, golden instants when art and faith converge.

The Crypt: Stillness and Reflection

Beneath the great body of the cathedral lies its most haunting space, the crypt. Built in the 11th century, it is low, cool, and dimly lit, its Norman arches sturdy as roots.

After heavy rain, a thin layer of water gathers across the floor, transforming the chamber into a mirror of stone.

At the far end stands Antony Gormley’s Sound II, a solitary bronze figure holding a shallow bowl, forever contemplating its reflection. It is one of the most photographed artworks in England, yet it never loses its power. The trick is not to copy but to listen again.

Compose your shot slowly. Allow the reflections to settle. Expose for the highlight on the water and let the shadows breathe. A vertical frame can accentuate the depth and solitude; a low, wide shot can immerse the viewer in that stillness. Resist over-editing. The quiet is the subject.

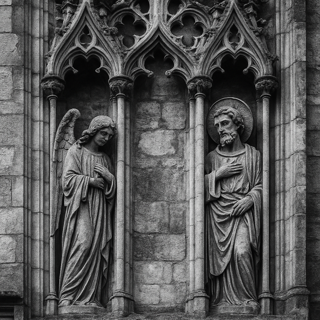

Outside: Buttresses, Flyers, and the English Sky

When you step outside, the cathedral reveals another face, one of structure, logic, and endurance. Walk the close in slow circles. From a distance, study the flying buttresses in profile; they are like stone wings frozen mid-flight, holding the weight of heaven. Move closer and trace the knapped flint and limestone blocks, their contrast of texture and tone.

The west front, broad and dignified, rewards frontal symmetry. But often the most interesting angles come from oblique views, where one transept cuts across another, or where the tower rises behind a foreground of cloister walls and yew trees. Winchester sits comfortably within its landscape, and the surrounding greens and gravestones add a quiet narrative.

At dusk, a slow handheld exposure will draw a hint of cobalt from the sky while the cathedral windows glow amber from within. After rain, puddles mirror the building’s geometry, and the pavement shines like polished slate. These are gifts to the attentive photographer, transient, humble, yet luminous.

Colour, Monochrome, and the Art of Restraint

Winchester invites both colour and black and white, each revealing a different truth. In colour, the cathedral breathes warmth and life. The stained glass radiates its stories; the late light gilds the stone. Maintain a consistent white balance and resist the temptation to oversaturate. Cathedral light is deliberate, subtle, architectural, and even theological. Too much manipulation can drown its quiet voice.

In monochrome, the story changes. Stripped of hue, the eye falls to line and form, to the conversation between dark and light. The rhythm of arches, the gradation from nave to choir, the glimmer of a candle in the gloom, all take on a timeless gravity. Let the blacks remain true and the grain honest. It suits the age of the place. The result can feel like a rediscovered memory rather than a modern photograph.

Respecting the Living Church

Above all, Winchester is alive. It is not a museum but a living church. Every photograph should honour that. Move softly. Avoid intruding on worshippers or services unless invited. Give space at altars and chapels. Some of the best photographs arise not from planned compositions but from small acts of reverence, waiting, listening, allowing the building to speak first.

There’s an unspoken etiquette among those who love photographing sacred spaces: you become invisible to let the place appear. Your tripod, if allowed, becomes an anchor rather than a statement; your camera, an extension of your respect.

And sometimes, put the camera down altogether. Sit for a while. Feel the cool air from the stone, the faint trace of incense, the shimmer of candlelight against glass. Photography begins with seeing, but true seeing begins with stillness.

A Personal Reflection

Every cathedral carries the spirit of its builders, but Winchester holds something deeper, the spirit of the land itself. It has stood witness to coronations and funerals, reformations and restorations, the hum of pilgrims and the silence of plague years. The tomb of Jane Austen rests quietly in the north aisle, the great author forever framed by the same play of light that once fell on monks and kings.

To photograph here is to engage in dialogue with history. You find yourself walking the same axis that countless others have walked, lifting your gaze to the same vaults that lifted theirs. Your camera becomes a bridge between centuries.

On my last visit, as evening closed in, I found myself alone near the font, the only sound the ticking of the heating pipes and the soft shuffle of a verger in the distance. I watched as the last shaft of sunlight fell across the nave, catching the dust in the air. For a few seconds, it felt as if the building breathed. I lifted the camera once more, not to capture, but to remember.

That is the gift of photographing Winchester Cathedral: it teaches you that the best images are not about exposure or lens choice, but about presence. About learning to stand in a place where time pools and to let it fill you, quietly, until you press the shutter.

Light, stone, and memory, that is Winchester’s trinity. And if you listen closely enough, your photographs may carry a little of its long, unbroken song.

Roland 'Roly' Keates

About the Author

Roland “Roly” Keates is a Derbyshire-based filmmaker, photographer, and historian whose work explores the intersections of place, memory, and light. A long-time documentarian of local heritage and sacred landscapes, he is the creator of the Custodians of the Woodland film series and Look Up to Derby, a visual journey through the city’s architecture.

Blending fine-art photography with historical research, Roly’s projects often weave together themes of spirituality, craft, and the enduring presence of the past within the English landscape.

His work has been exhibited regionally and featured in collaborative community projects across art, culture, and heritage. When not filming or editing, he can usually be found wandering woodland paths, camera in hand, waiting for the perfect meeting of light and story.

He is the Creator of the Custodians of the Woodland film series: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLr7M_vks5PajZ71vLjXNpTgEKR9Nbi4LG

Useful Links:

Winchester Cathedral official website https://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/

Art and Christianity listing Antony Gormley's Sound ll https://artandchristianity.org/ecclesiart-listings/antony-gorml ey-sound

Antony Gormley's official website https://www.antonygormley.com/works/sculpture/permanent

This article is published by Marysia Zipser, Founder & Ambassador of Art Culture Tourism & Keynote Speaker, Beeston, Nottingham. https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/ https://www.artculturetourism.co.uk/blog E: artculturetourism@gmail.com

Please feel free to write your feedback, remarks/reactions to Roly in the Comments box below, to which he will respond, and to share/forward this article/blog link via email to friends, colleagues and to socials as you wish. Thank you.